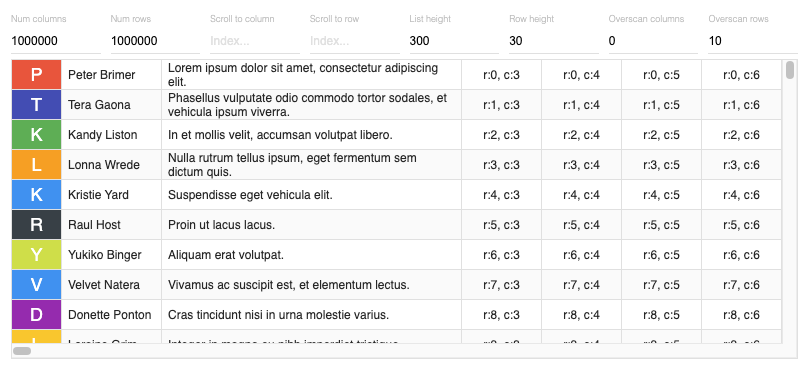

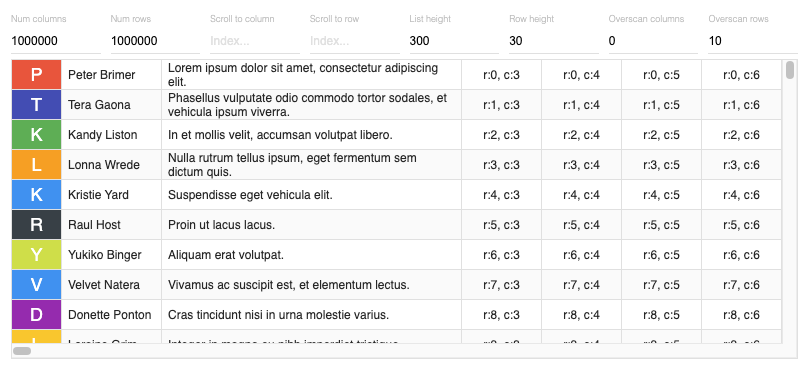

It turns out that implementing a grid control capable of scrolling over millions of rows and columns is much harder than I thought. The grid is virtualized, so the browser only has to deal with the cells visible in the viewport. Right now, there’s no data. The content of each cell is generated on the fly.

So why is this so difficult?

Two Problems

I’ve looked at lots of grid controls and keep running into the same two problems. First, there’s the limitations of the native browser scrollbar. All the major browsers have limits on the amount of virtual content you can scroll over. Currently that’s about 33 million pixels in Chrome and Safari, less in Firefox. That’s around a million rows or columns, less if your cells are bigger than 30 pixels high or wide. Most grid controls break if you go over that limit.

I only found one control, SlickGrid, with an acceptable workaround. Why don’t I use that? Let me introduce you to the second problem.

If you have a grid with millions of rows and columns, you need some way of dynamically binding to the data and metadata for each row, column and cell. The grid should only load what it needs to display the visible elements.

I like to categorize grid controls in levels. Many grids have no dynamic binding at all. You provide arrays of data and metadata to define cell content, row heights, column heights, formatting, etc. This is level zero. No use to me at all.

At level one you have controls with dynamic binding to row data. The number of columns and column metadata is statically bound. You can have millions of rows but not millions of columns. SlickGrid is a level one control.

Level two controls add dynamic binding for column metadata. You can have a million columns without needing to keep a million column definitions in memory. Controls at level two look like they should be able to handle millions of rows and columns but end up being limited by poor implementation choices. The react-virtualized Grid and react-window VariableSizeGrid are level two controls. They end up making O(n) queries for row and column metadata if you scroll to the bottom right corner.

Level three controls actually work with millions of rows and columns. No matter which part of the grid is visible in the viewport, the amount of work performed by the grid is always O(v) where v is the number of visible cells. The react-window FixedSizeGrid would be a level three control if it wasn’t limited by the maximum size of the native browser scrollbar.

What I Really Want

I want a flexible level three control with working scrollbars, per cell styling, variable size rows and variable size columns. Is that too much to ask? I’ve looked at a few more controls since last time, and it’s a losing game. Most are level zero or level one.

I’ve got bored of looking. Time to build my own.

High Range Scrollbars

Native browser scrollbars have limited precision. So why not implement my own custom scrollbar that can use all the precision available with JavaScript’s 64-bit floating point numbers? The consensus seems to be that it’s really hard. You need to try and match the look and feel of the native scrollbars across the major browsers on desktop and mobile platforms. You need to support all the standard ways of interacting: mouse, mouse wheel, keyboard, touch. You need to ensure that your control will be as accessible as the native one.

So hard, that I haven’t found a single fully custom scrollbar. There are lots of custom scrollbars out there but they all take one of two approaches. The simplest approach is to use CSS styling to alter the look of the native scrollbar. There are full featured browser specific extensions for webkit based browsers (e.g. Chrome and Safari), or more limited official standards (e.g. Firefox).

The other approach is to hide the native scrollbar while leaving it functional. Then provide your own visual representation of the scrollbar positioned on top. Use handlers for the native scroll events to update the look of the custom scrollbar.

Both approaches rely on native scrollbar functionality to do all the hard stuff, so don’t help with the precision problem. I think my best bet is to stick with native scrollbars and use SlickGrid’s paged scrolling approach to support large grids.

Data Binding Interface

I like the principles behind React-window. Build a minimal, flexible component that focuses only on the virtual scrolling problem. Let the app developer use whatever component they like for the individual cells. The grid’s responsibility is to respond to scroll events and decide which cells need to be rendered and where they should be placed in the viewport.

The problem with react-window is that it’s not minimal enough. The interface requires the app developer to provide the width and height of each cell. That means the grid has to add up the widths and heights to work out where to position each cell. If the viewport is positioned over the bottom right corner of the grid that’s an O(n) process.

The grid also needs the reverse mapping from offset to cell index. That means, once again, an O(n) process of adding up widths and heights until the desired offset is reached.

A more minimal interface would require the app developer to provide mapping functions between the cell indexes and the horizontal and vertical offset from the grid origin to the top left corner of the cell. Now all the grid control has to do is combine the supplied offsets with the offsets from its paged scrolling system.

Isn’t this just pushing all the complexity onto the app developer? Now they have to add up all the widths and heights, then figure out some kind of caching scheme to make performance tolerable. Well, let’s look at some specific scenarios and see how it works out in practice.

The simplest scenario is fixed widths and heights, which is trivial to implement. verticalOffset = rowHeight * rowIndex and horizontalOffset = columnWidth * columnIndex with the reverse mapping being equally simple. Next up in complexity we have a small fixed number of columns with non-standard widths and all the rest with the default width. We saw an example of this last time. The mapping functions are still pretty simple, you could do it with a switch statement, so O(1) complexity.

Let’s step up the complexity again to a spreadsheet scenario. In a spreadsheet all the cells start off with a default size until the size is adjusted by the user. In a million row and column spreadsheet, must cells will continue to have the default size. You don’t have to add up all the row and column sizes, just the non-default ones. The implementation is getting more complex, but still simpler and more efficient than the general implementation we saw in react-window’s VariableSizeGrid.

In the rare cases where you do need a general implementation based on a row/column size getter interface, you can combine the simple virtual scrolling grid with a complementary offset cache component. You shouldn’t need to pay the price unless you need it.

DOM vs Canvas

So far, all the implementations we’ve explored have been based on updating the DOM so that we end up with correctly styled cells, with the right content, in the right place, whenever we move the scrollbar. The browser then runs its full layout, composition and paint pipeline. That seems inefficient. If we have to work out exactly what needs rendering on every scroll event, why don’t we just draw it directly? After all, we’ve already seen that’s what Google Sheets does.

The obvious answer is that it’s a lot of work and I don’t have the size of team that Google Sheets does. It’s also a micro-optimization. I want something that will scale to millions of rows and columns. The hard part is making sure that you only load the data and metadata needed by the visible viewport. After that, optimizing the rendering of the viewport hardly moves the needle.

The same argument can be made against writing the most optimal vanilla JS DOM update routines. Do it the easy way by describing what you want and letting React figure out how to update the DOM. I’m also starting to appreciate the separation of concerns that is the natural outcome of breaking the problem down into separate React components. If I get it right, I can use existing components for the pieces that aren’t directly related to managing an enormous grid.

The Plan

I’m going to start with react-window, replace it’s data binding interface and integrate SlickGrid’s paged scrolling approach. I’m not going to start with a fork of react-window. Once I’ve changed the interface, any changes I make will never be merged back.

Instead, I’m going to use this as a learning experience. The plan is to build my own control from scratch, in Typescript. I’ll port features from react-window and SlickGrid as I go. This is a great opportunity to get my head round modern React with Hooks. All the production React code I’ve looked at uses the old class component approach. Meanwhile, the official React docs don’t mention class components at all until you hit the legacy APIs reference section at the end.