When we started on this journey, I told you that there was an easy way and a hard way to implement a database backed grid view. I then spent the next six posts in this series taking you through different variations of the hard way.

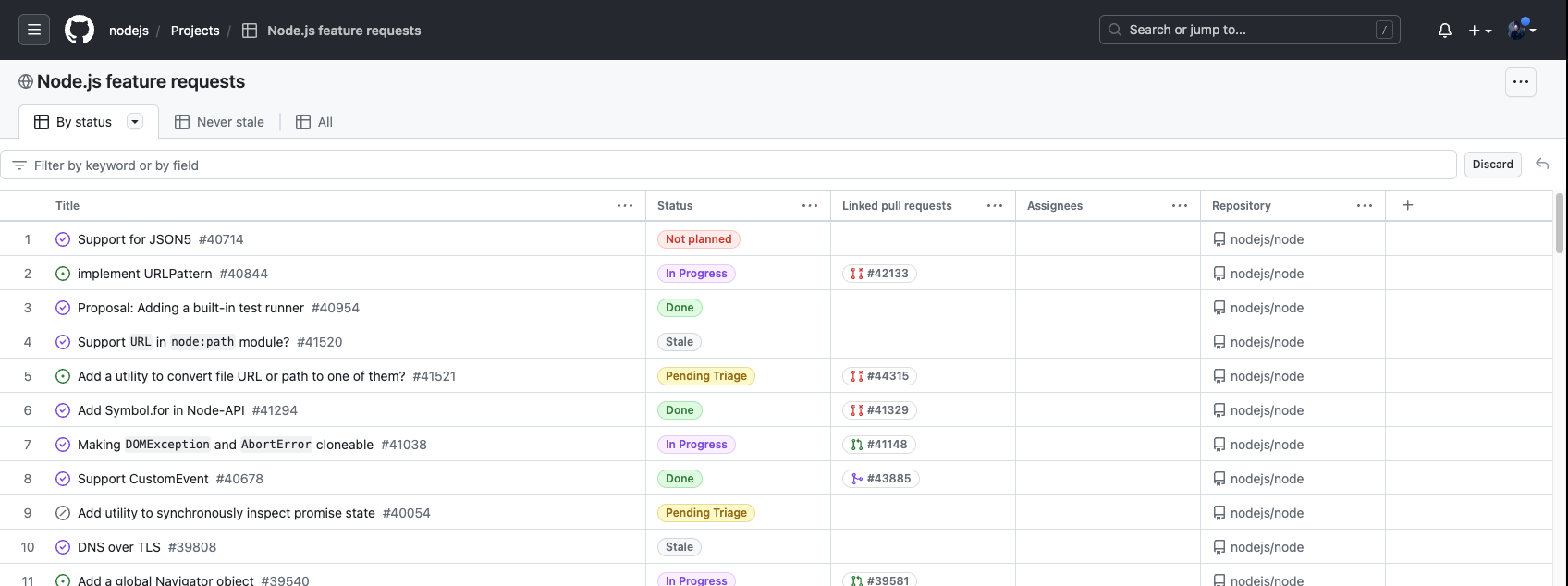

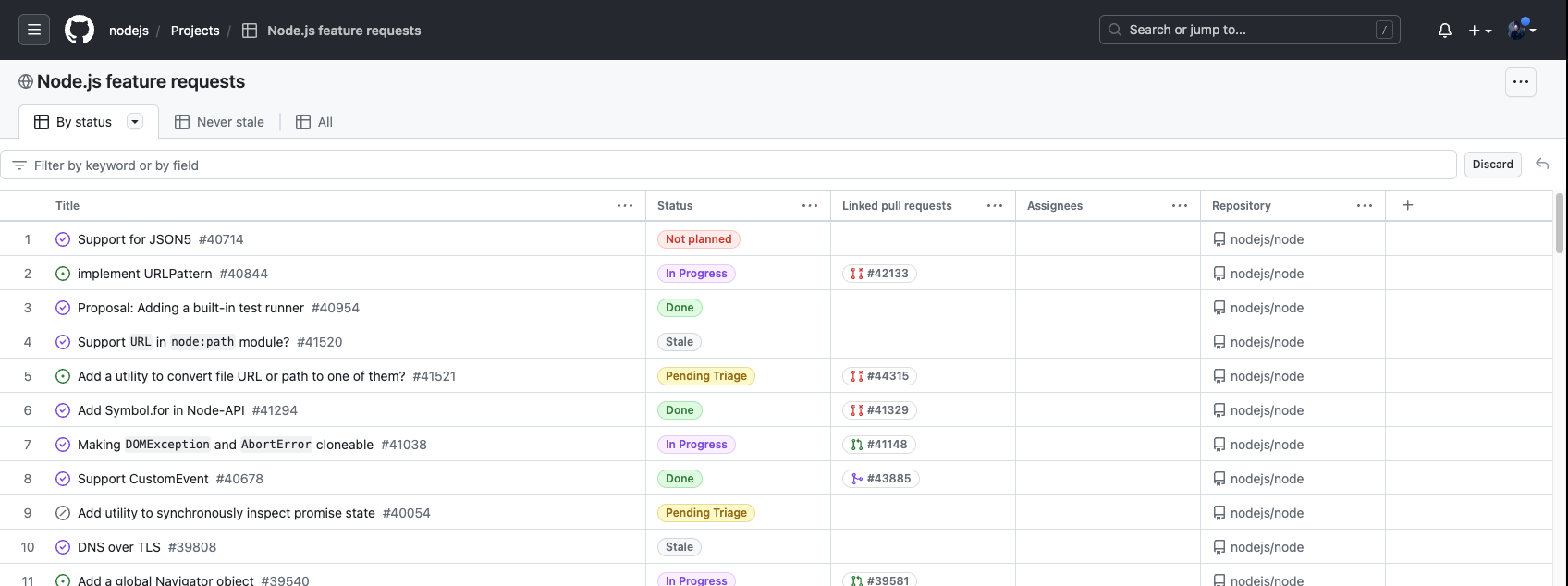

The problem with the easy way is that it relies on the collection of data you need to display in the grid view being small enough that you can load it all into the client and do all the sorting and filtering you want client side. For example, GitHub projects implements a grid view of issues the easy way by limiting the number of issues to at most 1200 and limiting each issue to 50 fields, where each field stores at most 1KB of data.

The GitHub client loads all the issues in the project up front. That’s 1200 of them for a maxed out project. A typical project with 10 fields averaging 100 bytes a field needs to download 1.2MB of data, which will take about a second over a basic 10Mbps ADSL broadband connection. A worst case project with 50 fields each using 1024 bytes of data needs to download 60MB, which would take 60 seconds to open.

That seems like a reasonable upper limit on project size. UX designers talk about the three response time limits of 0.1 seconds, 1 second and 10 seconds. A second to open or refresh a collection of issues is the limit for a user’s flow of thought to stay uninterrupted. Taking 60 seconds in the worst case is beyond the 10 second limit for keeping a user’s attention but is just about tolerable as a worst case scenario.

The easy way is not only simpler to implement but also gives the end user a vastly improved experience. Once the data is loaded, everything you do with it is well under the 0.1 second response time limit. Sorting and filtering feels effortless. Is there a way to make the easy way work with larger sets of data?

Before I answer that question, I need to take you on a little detour through the history of web client implementation.

Web 1.0

The early days of the web were characterized by content served up as static HTML pages. A paged database grid view was literally served up as separate html pages, with one page for the first fifty issues, a second page for issues 51 to 100 and so on. The UI for interacting with paged data took the form of explicit buttons to move between pages, just like posts in my blog.

Every interaction with the “web app” would result in a new page fetch, which in turn would fetch up-to-date data from the database. If a user had been staring at a page for some time, they could update it manually by using the refresh button in the browser.

As every interaction involves a round trip to the server, the app never achieves the 0.1 second response time required for the experience to feel fluid.

Single Page Apps

The dark days of web 1.0 were followed by the rise of single page apps. Instead of every interaction resulting in a new page load, the app uses JavaScript to fetch new data from the server and dynamically rewrite the current web page. The main HTML, JavaScript and CSS is fetched as a single page load at startup.

Data is fetched from the server using explicit API calls, most commonly using the REST pattern. The UI is more dynamic and cohesive. It feels more like a dedicated app than a set of web pages. Paged database grid views replace explicit pages with virtual scrolling. The user thinks they’re navigating seamlessly through a never ending list of issues, but in reality the app is loading the data that is about to scroll into view a page at a time behind the scenes.

Interactions with the app become more fluid. As long as the data is there, the elusive 0.1 second response time is achievable. However, if the user is doing something that consumes data faster than it can be fetched, the extra latency can be jarring.

In our case, the user is spending some quality time reviewing issues in their project. All the issues have been retrieved and the experience is fast and fluid. However, as time passes, the data they’re looking at becomes out of date, as other users work on issues. We no longer have the happy side effect of Web 1.0, where every interaction needs a page fetch which in turn refreshes the data.

Solving this problem is often an afterthought in the rush to put a functional app together and ship it. The single page apps I worked with adopted a variety of ad hoc approaches. You might poll the server every 30 seconds to see if anything has changed. If you were worried about the lack of responsiveness or the extra load that puts on the server you might look at server-sent events or web sockets so that the server can notify the client.

Even if you can work out that newer data is available, you still have the problem of updating the content in the app. The way you’ve stored the data in your database and exposed it via a REST API is designed for loading pages of data at a time. There’s no easy way to work out what has changed and retrieve just the data you need. Reloading everything will be disruptive to the user. You end up with kludgy solutions like putting up a banner to tell the user that there is new data, which reloads when clicked on.

Then, underlying everything, is the app’s dependence on an available, fast and stable network connection.

Progressive Web Apps

The driving idea behind Progressive Web Apps is to approach native app levels of functionality and performance. In particular, a progressive web app can continue to run if the network connection is lost or intermittent. Progressive Web Apps depend on modern browser features such as service workers and client-side storage.

Service workers sit between the app and the network with the ability to intercept, augment or replace all network requests. A Progressive Web App will typically download and cache all the app’s HTML, JavaScript, CSS and other resources on first use. On subsequent uses it will respond immediately with the cached resources, even if there is no network connection. The app can also use service workers to implement background data synchronization and pre-fetching of data that the user is likely to need.

Modern client-side storage APIs allow apps to store large amounts of complex data locally. This includes IndexedDB, a rich client side database, and Origin Private File System which gives your app full access to its own dedicated file system. OPFS has only been available across all major browsers since March 2023. Prior to that, apps would use IndexedDB or the Cache API to store file content locally.

Which all sounds great. Our app can pull down all of the data needed by the grid view and store it locally. After first use, everything is fluid and responsive. Data can be updated asynchronously in the background. But that stills leaves us with the problem of how to determine what has changed and retrieve just the data we need.

Event Sourcing

Enter Event Sourcing. I’ve discussed Event Sourcing in some detail in my series on implementing a cloud spreadsheet. The basic idea is simple. We store an ordered sequence of events which define all the changes made to the collection of issues. To load the data into the client, retrieve all the events and replay them locally.

Working out what has changed and retrieving the data needed is now trivial. The client knows the most recent event it consumed. It just needs to query the server for any events that have occurred since then.

The client can use IndexedDB to store the event log locally. When the app loads, load and replay the local events. Then check for any recent events from the server.

If required, it’s reasonably straightforward to add support for offline editing. Simply add events to the local IndexedDB event log. When network access is restored, forward the events to the server. Obviously you’ll need to implement some form of conflict resolution if changes have happened on the server while you were offline. Events are perfect for capturing user intent, which makes it easier to implement automated or semi-automated conflict resolution.

Eventually the event log will become too long to be manageable. Event Sourcing addresses that by creating snapshots at regular intervals. A snapshot captures the state of the issues collection at the corresponding point in the event log. Now to load data into the client, load the latest snapshot and then replay any events since the snapshot was taken.

Instant Resume

Let’s wind back to where we started. We want to use the easy approach to implementing a database backed grid view where everything happens client side. To make that work we have a 1200 issue limit on the size of a collection.

A Progressive Web App using Event Sourcing lets us store data locally and efficiently keep it in sync with changes on the server. However, we still need to wait to download all the data. What have we gained?

The point is that you only have to wait once, when you first open the collection. After that, everything is available locally with changes synced in the background. You can even sync snapshots in the background. Just keep loading from the previous snapshot until the latest has downloaded.

What would happen if we increased the limit to 12000 issues? Our typical project would take 10 seconds to open the first time you used it. The worst case project would take 10 minutes. That’s go and have a cup of coffee long. However, you only have to do it once. If you start working with a project right from the beginning, you never have to wait.

Client-side Storage

Is there a technical limit on how large a project can be if users are prepared to wait on first use? After all, people are prepared to wait for hours to install gigabytes of content for a game.

All browsers have a limit on the amount of client-side storage space that an app can use, shared by all client-side storage APIs. The limit varies between browsers but all support at least 1GB of data. Apps can request more space, which may require confirmation from the end user.

| Browser | Default | On Request |

|---|---|---|

| Chrome/Edge | 60GB | 60GB |

| Firefox | 10GB | 50GB |

| Safari | 1GB | 200MB per request |

Most browsers base the limit on the size of the disk drive that contains the user’s profile data. In the figures above I’ve assumed that the drive will be at least 100GB.

The worst case project for 1200 issues is 60MB of data. We can manage 20 times that across all browsers, or 200 times if we can ignore Safari.

Compression

If we need to transfer and store 12000 issues, each with 50 fields using 1024 bytes per field, we need 600MB, right? Wrong. This is highly structured and correlated data which should compress really well. With a REST API returning a small page of data encoded as JSON, compression doesn’t get you much. With a synchronous request-response API, you can’t do much more than gzip the response and get back what you lost from using a text encoding like JSON.

An event sourcing snapshot has two advantages. First, it can take account of all of the data in the collection. Second, creating a snapshot is an asynchronous process. You can take as long as you need to organize and compress the data for efficient transfer and load.

Compressing all the data at once is huge. Even if all you do is represent it as one big gzipped JSON file, you can expect 10X compression.

Our data isn’t random JSON. It’s a highly structured array of issues where each issue has fields with a consistent set of types. We can get even better compression by using a column oriented representation. Rather than arranging the snapshot as an array of issue structures, we use a structure of arrays, one array for each field. Each array contains values with the same type, often with very similar values. This rearrangement improves compression by itself. On top of that, you can use type specific compression like varint and delta encoding. On the right data, Delta+Varint+GZip can achieve 50X compression.

Let’s be conservative and say that we can reliably achieve 10X compression with the right snapshot format. Does that mean we can increase the limit another 10X and support 120,000 issues?

Memory Consumption

It doesn’t matter how well we compress the data if we have to load it all into memory and uncompress it. Our worst case project would need 6GB of memory for 120,000 issues, plus whatever overhead the memory management system and web browser runtime adds.

The amount of memory available to a web app is dependent on the combination of browser and operating system in use. If either the browser or operating system is 32-bit, you will be limited to at most 2GB. The 64 bit version of Chrome is still limited to 4GB of heap memory per tab. Limits on mobile devices are typically even lower.

Ideally we would keep our working set to around 1GB for maximum compatibility. Is there anyway to reduce the amount of data we have to keep in memory?

Sorted String Tables

We need enough data in memory that we can support sorting and filtering on any column in our grid view. We can use virtual scrolling to limit the amount of data that has to be loaded for display. However, that doesn’t help if we need all the data loaded anyway to sort it.

The real problem is the 1024 byte maximum size for string fields. All the other types of field need at most 8 bytes. If we could limit string fields to 8 bytes of permanently loaded data, the worst case memory requirement comes down to 400 bytes per issue. Let’s round that up to 512 bytes to account for fixed fields and any other per issue overhead. Then 120,000 issues would only need 60MB of memory.

The trick, like so often in computer science, is to add another level of indirection. Rather than storing strings directly in the array of values for each field, we store them in a separate sorted string table. As the name implies, all the string values in the snapshot are deduplicated and written into the table in sorted order. Each string can be identified by a 32 bit integer index. We’re now dealing with arrays of integers for each field.

We keep the arrays of integers in memory and only load the strings they reference when needed. Aren’t they all needed when sorting? They’re not needed at all. The strings are stored in sorted order, which means the indexes sort in the same order as the strings. We only need to load the strings for display using virtual scrolling.

Storing the strings separately and loading them on demand can also reduce the time needed when first opening a project. The worst case scenario is now downloading 60MB of data, compressed 10X. We’re back under 10 seconds. The string table can be divided into chunks which are downloaded on demand and in the background.

Which is all great, if all we were doing is loading a snapshot. What about the events that occur after the snapshot was created? What about strings created or changed by local edits? We can easily modify the arrays in memory but it’s not practical to update the string table.

Whenever we have a new string, we see if it already exists in the string table. We can do the lookup efficiently using binary chop. If it already exists, we can represent the string using the string table index we found.

If it doesn’t exist, we represent the string using a three part identifier. The first two parts are the event that the string is defined in and the field within the event. We can encode that in four bytes. We need 6 bits to identify one of 50 fields, which leaves 26 bits to identify an event out of those added to the event log since the last snapshot. The third part is the index of the string that would come immediately after this one, if it was inserted in the string table.

There are three cases to consider when comparing strings during a sort.

- Both strings are in the string table. Just compare their string table indexes.

- One string is in the string table, the other is new. Just compare their string table indexes. If the indexes are equal, we know the new string comes first.

- Both strings are new. Compare their string table indexes. If the indexes are equal, and only then, load the strings and directly compare them.

Typed Arrays

There’s one more improvement we can make. We’ve carefully structured the snapshot as a set of arrays, one per field. Each array contains values of a fixed type with a fixed size. We can use the same representation in memory by loading each array into a JavaScript typed array. This is far faster and more memory efficient than using a JavaScript object for each issue.

As an added bonus, the memory used by typed arrays doesn’t count against the 4GB per tab heap memory limit in Chrome.

Scalability

Event sourced systems can be extremely scalable. Apart from the occasional snapshot update, you’re not transferring the same data over and over. With a bit more effort, you can use segmented snapshots which can be incrementally updated, rather than writing a complete snapshot from scratch each time.

Event sourced systems don’t need complex back-end databases, especially when using a full fat client, as we are here. Completely serverless implementations using DynamoDB, S3 and Lambda (or the non-AWS equivalents) are possible. Those things scale horizontally incredibly well. If you store the snapshots in S3 you can use a CDN like CloudFront to reduce latency and scale delivery even further.

Conclusion

We started with what seemed like an insurmountable problem. Taking GitHub projects as an example of a fully client side database grid view implementation, and finding a way to extend past their limit of 1200 issues per project.

We’ve ended up with an architecture which should be able to handle close to a million issues. Getting there took a total rethink of how the front end and back end work. A real focus on how the data is accessed and what that means for how it is stored, transferred and loaded into memory. A true full-stack approach.

Will it actually work? While I haven’t implemented this myself, I have been closely involved with systems that use similar principles. The Autodesk Platform Viewer effectively creates snapshots from 3D CAD models containing millions of triangles, which can then be loaded into a web app. It always struck me as absurd that I could interact fluidly with a 3D model containing a million objects but struggle when accessing a grid view containing a few thousand.