Last time, we created the basic structure for our scalable virtual scrolling controls built with modern React and TypeScript. The next job is to put a scalable data binding interface in place. We want the rendering costs for our controls to be proportional to the number of visible items, rather than the total number of items being scrolled over. We can’t control how the data and metadata being displayed is retrieved and managed, but we can make sure that the interface we provide is as efficient as possible.

The data interface we copied over from react-window is fine. The control instantiates an instance of its child component for each visible item and passes in the item index. The host app can use whatever mechanism it likes to retrieve data for that index. Where it all goes wrong is the metadata interface used to determine the size of each item and the offset that positions it within its parent.

The react-window interface is elegantly simple, a getSize function that returns the size of an item. The problem is that working out the offset to position an item requires adding up the sizes of all preceding items.

The solution is to expose a more fully featured interface that lets the app provide an efficient implementation tailored to its requirements.

The Item Offset Mapping Interface

Modern React is functions all the way down. It seems kind of old fashioned to define an interface that will be implemented by a class. I spent more time thinking about this than it warranted. In the end I decided it would be contrived and overly verbose to require three function props which would each need to capture some state that defined item sizes. Cleaner to gather it all together in an object.

export interface ItemOffsetMapping {

itemSize(itemIndex: number): number;

itemOffset(itemIndex: number): number;

offsetToItem(offset: number): [itemIndex: number, startOffset: number];

};

The itemSize and itemOffset methods are straightforward. For a given index return the size of the item and the offset that positions it. The third method needs more explanation. As mentioned previously, we also need to map the other way, from an offset to the corresponding item. The control uses this to determine the first visible item given the current scroll offset. As well as the index of the item, the rendering code also needs to know the actual start offset for the item (as opposed to the scroll offset we’re querying with).

The obvious thing would be to have offsetToItem return just the index of the item and have the rendering code call itemOffset to get the actual offset. Why make the interface more complex by having offsetToItem return both?

For any non-trivial implementation, offsetToItem is the most expensive call in the interface. The implementation will have some kind of data structure that maps item index to offset for a set of items. Querying the data structure will involve a binary chop or tree traversal with an O(logn) query cost and will naturally determine both index and offset. In many implementations, itemOffset will end up querying the same data structure, doubling the cost for the simpler interface.

Fixed Size Item Implementation

The fixed size item implementation is as simple as you would expect.

class FixedSizeItemOffsetMapping implements ItemOffsetMapping {

constructor (itemSize: number) {

this.fixedItemSize = itemSize;

}

itemSize(_itemIndex: number): number {

return this.fixedItemSize;

}

itemOffset(itemIndex: number): number {

return itemIndex * this.fixedItemSize;

}

offsetToItem(offset: number): [itemIndex: number, startOffset: number] {

const itemIndex = Math.floor(offset / this.fixedItemSize);

const startOffset = itemIndex * this.fixedItemSize;

return [itemIndex, startOffset];

}

fixedItemSize: number;

};

Get Range To Render

I had to completely rewrite the getRangeToRender method that I inherited from react-window. The original had too many assumptions about fixed size items baked in.

type RangeToRender = [

startIndex: number,

startOffset: number,

sizes: number[]

];

function getRangeToRender(itemCount: number, itemOffsetMapping: ItemOffsetMapping,

clientExtent: number, scrollOffset: number): RangeToRender {

if (itemCount == 0) {

return [0, 0, []];

}

var [itemIndex, startOffset] = itemOffsetMapping.offsetToItem(scrollOffset);

itemIndex = Math.max(0, Math.min(itemCount - 1, itemIndex));

var endOffset = scrollOffset + clientExtent;

const overscanBackward = 1;

const overscanForward = 1;

for (let step = 0; step < overscanBackward && itemIndex > 0; step ++) {

itemIndex --;

startOffset -= itemOffsetMapping.itemSize(itemIndex);

}

const startIndex = itemIndex;

var offset = startOffset;

const sizes: number[] = [];

while (offset < endOffset && itemIndex < itemCount) {

const size = itemOffsetMapping.itemSize(itemIndex);

sizes.push(size);

offset += size;

itemIndex ++;

}

for (let step = 0; step < overscanForward && itemIndex < itemCount; step ++) {

const size = itemOffsetMapping.itemSize(itemIndex);

sizes.push(size);

itemIndex ++;

}

return [startIndex, startOffset, sizes];

}

This version uses offsetToItem to find the first visible item and offset. It then iterates through the following items, adding up their sizes, until it hits an item outside the visible window. The function returns the start index and offset, together with an array of sizes for each visible item.

Overscan items add additional complexity. These are additional items outside the visible window that are also rendered. By default, react-window adds one overscan item before the first item and after the last item. These are needed to ensure that tabbing between items works correctly. Once you tab to an item out of view, the browser will scroll it into view, triggering a render and the creation of more items. Without the overscan items, you would be unable to tab through the entire list.

React-window has props that allow the app to configure additional overscan items which in theory improve responsiveness when scrolling down a line or page at a time. I haven’t implemented that yet but the code is structured to make it easy to add.

Rendering Items

Item rendering is not much different to the previous implementation. Instead of iterating from first to last index, the code iterates through the array of sizes and uses it to determine the size and offset for each item.

function renderItems(props: VirtualListProps, scrollOffset: number) {

const { children, itemData = undefined, itemCount, itemOffsetMapping, height,

itemKey = defaultItemKey } = props;

const [startIndex, startOffset, sizes] =

getRangeToRender(itemCount, itemOffsetMapping, height, scrollOffset);

const items: JSX.Element[] = [];

var offset = startOffset;

sizes.forEach((size, arrayIndex) => {

const index = startIndex + arrayIndex;

items.push(

React.createElement(children, {

data: itemData,

key: itemKey(index, itemData),

index: index,

style: { position: "absolute", top: offset, height: size, width: "100%" }

})

);

offset += size;

});

return items;

}

Keeping getRangeToRender and renderItems as separate functions separates concerns and keeps the code simple. I’m also looking ahead to when I implement a grid control. I should be able to reuse getRangeToRender and call it twice, once to determine the columns to render, and once to determine the rows.

Variable Size Item Implementation

To demonstrate the generality of the interface and rendering implementation, I added a simple implementation for variable sized items. This is intended for the use case where the initial few items have different sizes with all the rest having a standard size. You could imagine using this for header rows, or the example grid we looked at previously with a small fixed number of columns with non-standard widths.

To use the mapping you provide a default item size and an array of sizes for the initial items.

class VariableSizeItemOffsetMapping implements ItemOffsetMapping {

constructor (defaultItemSize: number, sizes: number[]) {

this.defaultItemSize = defaultItemSize;

this.sizes = sizes;

}

itemSize(itemIndex: number): number {

return (itemIndex < this.sizes.length) ? this.sizes[itemIndex] : this.defaultItemSize;

}

itemOffset(itemIndex: number): number {

var offset = 0;

const length = this.sizes.length;

if (itemIndex > length) {

const numDefaultSize = itemIndex - length;

offset = numDefaultSize * this.defaultItemSize;

}

for (let i = 0; i < length; i ++)

{

offset += this.sizes[i];

}

return offset;

}

offsetToItem(offset: number): [itemIndex: number, startOffset: number] {

var startOffset = 0;

const length = this.sizes.length;

for (let i = 0; i < length; i ++) {

const size = this.sizes[i];

if (startOffset + size > offset) {

return [i, startOffset];

}

startOffset += size;

}

const itemIndex = Math.floor((offset - startOffset) / this.defaultItemSize);

startOffset += itemIndex * this.defaultItemSize;

return [itemIndex+length, startOffset];

}

defaultItemSize: number;

sizes: number[];

};

The assumption is that the array of sizes is small, so I haven’t bothered optimizing the implementation. For example, you could convert the array of sizes into an array of offsets when the implementation object is constructed. Currently each call to itemOffset or offsetToItem has to iterate through the array adding up the sizes.

Sample App

How much of this complexity is exposed to the hosting app? Let’s have a look.

const Cell = ({ index, style }: { index: number, style: any }) => (

<div className={ index == 0 ? "header" : "cell" } style={style}>

{ (index == 0) ? "Header" : "Item " + index }

</div>

);

function App() {

var mapping = useVariableSizeItemOffsetMapping(30, [50]);

return (

<div className="app-container">

<VirtualList

height={240}

itemCount={100}

itemOffsetMapping={mapping}

width={600}>

{Cell}

</VirtualList>

</div>

)

}

I’ve provided a hook style function that creates and returns the implementation object, hiding the internal details. This would also be a great place to add memoization or caching of the implementation object.

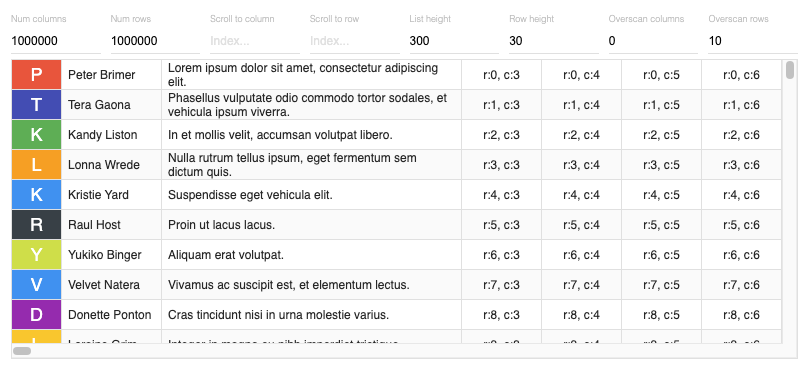

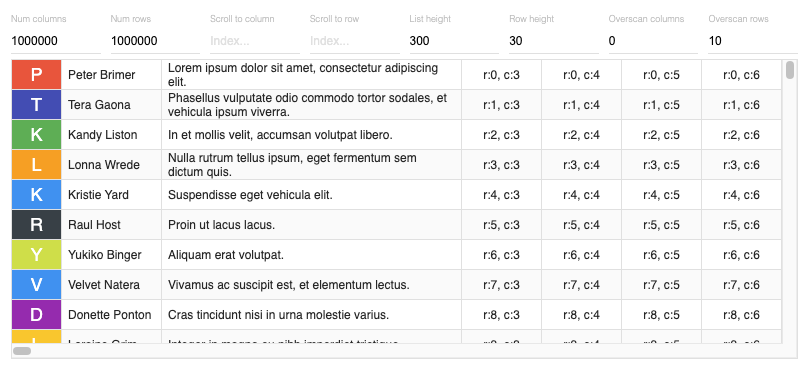

The sample app treats the first item in the list as a header with a large font which needs a larger size item.

Try It!

Next Time

The thrills don’t stop here. Next time we’ll continue with the core list functionality, setting us up to move onto grids.