Let me take you back to a time before NoSQL, when E.F. Codd’s relational rules and normal forms were the last word in database design. Data was modelled logically, without redundant duplication, with integrity enforced by the database.

To the sceptic, a normalized database is a design that divides the data into as many different tables as possible, regardless of what that means for efficiency and performance. To the believer, a normalized database is an elegant representation of the problem domain that ensures referential integrity and avoids the need for large scale rework as the design evolves over time.

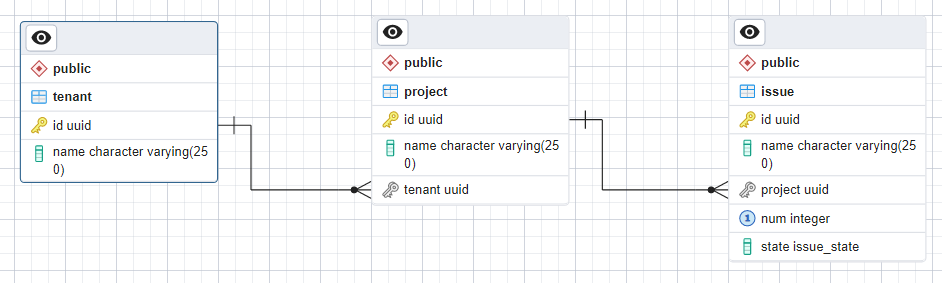

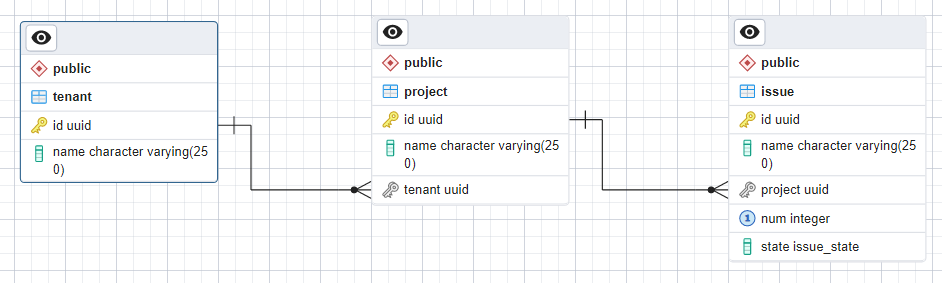

Here’s a basic data model for the GitHub Project Issues example of a Grid View that we looked at last time. The image is from the Postgres database ERD design tool. We’re starting off simple. No custom fields and only a handful of hard coded fields. I’ll be using Postgres for my examples, but the same basic principles apply to any relational database.

Schema

There are three tables: tenant, project and issue. There is a 1:many relationship between tenants and projects, and another between projects and issues, each enforced by a foreign key constraint. Each entity has a name and an id. That’s it for tenants and projects.

You might be tempted to try and simplify the design. Do you really need three separate tables?

The key to a normalized design is that the columns in each table are independent of each other. There are no constraints that mean a specific value in one column requires a corresponding value in another column. If there are, that’s a sign that there’s a subset of columns that should be broken out as a separate table. That means, for example, that you couldn’t eliminate the tenant table by adding a tenant name column to the project table. Tenant name is dependent on tenant id. We would be redundantly storing that information on every project in the tenant.

As your design evolves over time you will also find that you need to add additional columns to tenant and project. Best to start with a clean design up front that makes it easy to do so.

Issue is a little more interesting. As well as name and id we have an issue number and state. GitHub issues each have a number that is unique within a project and a state that is either open or closed. I’ve modeled state as a Postgres enum type so that it’s easy to add more types in future. I’ve also added a UNIQUE constraint to ensure that each row in the table has a unique combination of project id and num.

Keys

The keen eyed amongst you will have noticed that I’m using UUID primary keys. The type of key you use is often a hotly contested debate.

First off, do you use a natural or surrogate key? A natural key is one that already exists in the data you’re modelling. For example, you could use name as a natural key for a tenant. A natural key imposes a uniqueness constraint on the data. If we used (project,num) as a natural composite key for the issue table, we wouldn’t have needed to add a separate unique constraint.

The down side of a natural key is that changes in requirements can be hard to cope with. For example, if the business rules change so that the natural key is no longer unique, or if the format of data included in the key has to change. This can be particularly painful in a microservices world where keys from one service may be stored in another. For example, the business may decide that it needs to support the ability to merge projects. Which means renumbering the issues from one of the projects.

In contrast, a surrogate key is entirely independent of the data being modelled. You need an extra column to store a surrogate key but in exchange you know that changes in business rules won’t have any impact.

Once you’ve decided to use a surrogate key, you need to decide what data type to use for the key. There are three commmon choices: integer (32 bits), bigint (64 bits), or uuid (128 bits). With integer and bigint keys, the database system allocates a key for newly created data, usually using a sequence counter.

You may be tempted to start off with an integer key. Two thousand million rows seems like plenty. You can always change it later if your application is a massive success and you start to run out of ids.

Don’t. I’ve lived through too many crises caused by running out of integer ids. The small amount of space you’re saving is never worth the potential future pain. In the worst case, the team running the service doesn’t realize they’re running out of ids until the system refuses to create new records. In the best case, you spot what’s happening in time. Then you find out just how painful it can be to change the primary key column of a two thousand million row table.

UUID stands for Universally Unique Identifier. Anyone can create a UUID and, if they follow the rules, be confident that for all practical purposes it will not duplicate one that has already been or will later be created.

Using a UUID is the ultimate in future proofing. If your application scales to the point where you need to migrate to a database cluster, each individual server in the cluster can allocate their own keys knowing that they won’t conflict with those from another server. If you add support for a mobile client with offline working, it will be safe for the client to generate keys for newly created records, knowing that they won’t conflict with keys created by the database or other clients.

The down side for UUIDs is performance. They’re twice the size of a bigint and more expensive to index as they’re essentially random values. However, the difference is less than you might think. Around 25% in both size and performance for the worst case of a single column table that just contains ids. Reducing rapidly as you add more columns.

Most systems I’ve worked with have used UUIDs and never regretted it.

Sample Data Set

Let’s make this more concrete by populating our tables with some sample data. To keep the samples readable I’m only showing the first 4 digits of each UUID, feel free to generate the other 28 digits yourself.

tenant

| id | name |

|---|---|

| 0807 | ACME Engineering |

| 3cc8 | Big Media |

We have two customers for our issue tracking system, each with their own tenant.

project

| id | name | tenant |

|---|---|---|

| 35e9 | Forth Rail Bridge | 0807 |

| 7b7e | The Daily News | 3cc8 |

Each of our tenants has a single project. The engineering company has a contract to maintain the Forth Rail bridge, while the media company is working on the launch of a new newspaper.

issue

| id | name | project | num | state |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 020e | Needs Painting | 35e9 | 1 | open |

| 3544 | Launch new newspaper! | 7b7e | 1 | closed |

| 67d1 | Check for rust | 35e9 | 2 | closed |

| 83a4 | Hire reporter for showbiz desk | 7b7e | 2 | open |

| af34 | Girder needs replacing | 35e9 | 3 | open |

Looks like both projects have only just got started. Notice how the table contains issues from both projects and both customers mixed together.

Access Patterns

What access patterns do we need to support? Obviously we need to support CRUD on individual tenants, projects and issues. Easy enough to create, read, update and delete individual entities addressed by their primary key. The database automatically creates a primary key index for efficient lookup.

The interesting bit is querying collections of entities. I’m going to focus on issues within a project. The same concerns and solutions will apply to other collections like projects in a tenant.

The core query needs to retrieve issues in a specific project, ignoring those from other projects and tenants. You query a relational database by writing statements in SQL.

SELECT * FROM issue WHERE project = '7b7e';

which results in

| id | name | project | num | state |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3544 | Launch new newspaper! | 7b7e | 1 | closed |

| 83a4 | Hire reporter for showbiz desk | 7b7e | 2 | open |

We need the ability to sort the issues in the grid on one or more columns. For example to group by state and then sort by num in descending order.

SELECT * FROM issue WHERE project = '35e9' ORDER BY state ASC, num DESC;

which results in

| id | name | project | num | state |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| af34 | Girder needs replacing | 35e9 | 3 | open |

| 020e | Needs Painting | 35e9 | 1 | open |

| 67d1 | Check for rust | 35e9 | 2 | closed |

API

You will define an API. Doesn’t matter what style you use, whether that’s REST or gRPC or GraphQL. Your API will be a simple wrapper around the database queries.

Pagination

So far, so trivial. Remember the limits we defined last time. The PM would like us to support at least one hundred thousand issues per project. That’s too many to load in one go. We need to paginate the results from the database so we can retrieve them a manageable sized set at a time.

You need to choose an appropriate page size that balances load on the database, amount of data to transfer across the network and number of calls the client needs to make to get all the data. Somewhere between 50 and 500 items is typical. On the client side, old school apps will include explicit pages in their UI with Prev and Next buttons (just like the posts section of this blog). More modern apps will have some kind of virtualized UI, where more issues are loaded as you scroll down the grid view.

There are two standard ways of implementing pagination. The simplest, most widely used, and unfortunately least scalable is Limit-Offset. You can add a LIMIT clause to any query to limit the maximum number of records that will be returned. You can add an OFFSET clause to any query to skip a number of records before you start returning results. You can then paginate any query by repeatedly calling it with increasing offsets.

SELECT * FROM issue WHERE project = '35e9' ORDER BY state ASC, num DESC OFFSET 0 LIMIT 100;

SELECT * FROM issue WHERE project = '35e9' ORDER BY state ASC, num DESC OFFSET 100 LIMIT 100;

SELECT * FROM issue WHERE project = '35e9' ORDER BY state ASC, num DESC OFFSET 200 LIMIT 100;

...

The problem is that the database literally implements OFFSET by skipping records. To query the last page of 100,000 records, the database will retrieve 100,000 records, discard the first 99,900 and then return the last 100. Retrieving all the pages is at best an O(n2) operation, and frequently worse.

The more scalable, but more complex and less flexible approach is Keyset Pagination. Instead of using offsets to define where each page starts, you use the value of the first record in the page. How do you know what the first record in each page will be? You look at the last record in the previous page and setup a query for whatever comes next. It’s more complex because you have to adjust the query depending on what was on the previous page. It’s less flexible because you have to iterate through the pages one by one. You can’t jump directly to a desired page.

SELECT * FROM issue WHERE project = '35e9' ORDER BY num LIMIT 100;

SELECT * FROM issue WHERE project = '35e9' AND num > 100 ORDER BY num LIMIT 100;

SELECT * FROM issue WHERE project = '35e9' AND num > 205 ORDER BY num LIMIT 100;

...

In this example we’re sorting and paginating by num. Issue num is unique within a project so the query for the next page is for something greater than the last value on the previous page. There may be gaps where issues have been deleted, so even in this case you have to iterate through the pages one by one.

If you’re sorting on a column that isn’t unique, like state, keyset pagination is more complex. How do you handle the case where the range of duplicate values crosses a page boundary? The simplest solution is to also sort on another column that is unique, and gives an order that makes sense to the user.

SELECT * FROM issue WHERE project = '35e9' ORDER BY state, num LIMIT 100;

SELECT * FROM issue WHERE project = '35e9' AND (state,num) > ('open',235) ORDER BY state, num LIMIT 100;

SELECT * FROM issue WHERE project = '35e9' AND (state,num) > ('closed',57) ORDER BY state, num LIMIT 100;

...

Here the last records in each page are (open,235), (closed,57), (closed,211).

The most complex thing about Keyset Pagination is making sure you have the right index in place. Without that, it can be just as inefficient as Limit-Offset.

How do you make sure the right index is in place? I’m glad you asked.

Indexing

The best thing about a relational database is that you just give it a logical description of the data you want, and the database figures out how to get it.

That’s also the worst thing about a relational database.

It’s easy to get started, once you’ve figured out how to ask the database for what you want. Performance seems like a non-issue, everything works great. Then as your application starts to grow, you hit a brick wall. The database is overloaded, performance has tanked.

Never put a database query into production until you understand how the database will execute it. Fortunately, there’s an easy way to find out. Stick the EXPLAIN keyword before any query and the database query planner will tell you how it will be executed. The planner may decide to scan through all the rows in a table, looking for the one you want. It may use an index (if available) to find the rows you want more quickly. If you want sorted output, it may gather together all matching rows and sort them at the end, or use an index which already has the data you want sorted the way you want it.

If, like me, you’re playing around with a schema using some toy examples, you need to be careful. The planner may decide to use a sequential scan instead of an index because there’s not enough data to justify the overhead of an index lookup. Postgres has configuration parameters that can be used to encourage the planner to use an index if possible. You can then understand how the database would scale to large data without having to create a large test data set.

SET SESSION enable_seqscan=0;

SET SESSION enable_sort=0;

If you’re building a multi-tenant system, at a minimum you need an index that ensures that no query ends up scanning through every tenant’s data. There’s nothing worse than explaining to a customer that an application is slow because of something that other customers are doing.

In our case, we also want to make sure that any query for issues in a specific project doesn’t end up scanning through every other project’s issues too.

If you’re using pagination over large data sets, you need an index with the data sorted the way you want it. If not, the database will retrieve all 100,000 issues in a project, sort them, then iterate through to find the right page of 100 issues. Then do it all over again another 999 times to return the other pages. A process that scales as O(n2logn).

Enough preamble. Just how efficient were those queries we’ve been using?

Issues in a Project

EXPLAIN SELECT * FROM issue WHERE project = '7b7e';

Index Scan using issue_project_num_key on issue (cost=0.14..8.16 rows=1 width=556)

Index Cond: (project = '7b7e'::uuid)

There’s a lot of details in the EXPLAIN output that you can read about in the documentation. All we care about for our purposes is whether an index was used and whether there is any expensive additional processing like sorting.

In this case we’re all good. There’s an index that the database can use to find issues in a project. In this case I didn’t create the index explicitly. The database created it for me when I setup the unique constraint on (project,num).

Issues in a Project grouped by state and ordered by num

EXPLAIN SELECT * FROM issue WHERE project = '35e9' ORDER BY state ASC, num DESC;

Sort (cost=8.16..8.17 rows=1 width=556)

Sort Key: state, num DESC

-> Index Scan using issue_project_num_key on issue (cost=0.13..8.15 rows=1 width=556)

Index Cond: (project = '35e9'::uuid)

What about the fancier query where I grouped by state and then ordered by num? The database can still use the (project,num) index to find the issues in the project but now it needs to add an explicit sort step. That’s not going to work out well if we’re paginating this query over a large number of issues.

KeySet Pagination for Issues in a Project ordered by num

EXPLAIN SELECT * FROM issue WHERE project = '35e9' AND num > 1 ORDER BY num LIMIT 1;

Limit (cost=0.13..8.15 rows=1 width=556)

-> Index Scan using issue_project_num_key on issue (cost=0.13..8.15 rows=1 width=556)

Index Cond: ((project = '35e9'::uuid) AND (num > 1))

My first KeySet Pagination example does work. I’m sorting by issue num within a project, so the (project,num) index has the issues in the order I want.

Issues in a Project grouped by state and ordered by num with dedicated index

Let’s try and fix my “group by state and order by num” query by adding an explicit index.

A common mistake is to create indexes on individual columns. For example, one on state and one on num.

This is worse than useless. If you’re lucky the database will just ignore them. If you’re unlucky the database will use them and end up iterating across all issues with the specified state in all projects and tenants, then filtering out the 99.999% of issues that aren’t in the right project.

I need a multi-column index on (project,state,num).

EXPLAIN SELECT * FROM issue WHERE project = '35e9' ORDER BY state ASC, num DESC;

Sort (cost=8.16..8.17 rows=1 width=556)

Sort Key: state, num DESC

-> Index Scan using issue_project_state_num_idx on issue (cost=0.13..8.15 rows=1 width=556)

Index Cond: (project = '35e9'::uuid)

That’s weird. It’s using the new index, but only to find issues in the project. It’s still using an explicit sort step.

The problem is that the index orders issues by state and num both in ascending order. My query was for state in ascending order and num in descending order.

We’re hitting the limits of what we can feasibly support. Arbitrary sorting on two or more columns isn’t practical. Not only do you have the combinatorial explosion of dedicated indexes for each combination of columns, you also need additional indexes when sorting columns in opposite orders.

KeySet Pagination for Issues in a Project ordered by (state,num)

A reasonable limitation for Grid Views of large collections is to be able to sort by only a single column at a time. That needs a dedicated index for each column to support efficient KeySet pagination. Remember, for columns that contain duplicate values, the index should include an additional unique column to ensure there’s a sensible fixed order. For our issues example, (state,num) should work well.

EXPLAIN SELECT * FROM issue WHERE project = '35e9' AND (state,num) > ('open',3) LIMIT 1;

Index Scan using issue_project_state_num_idx on issue (cost=0.13..8.15 rows=1 width=556)

Index Cond: ((project = '35e9'::uuid) AND (ROW(state, num) > ROW('open'::issue_state, 3)))

Look at that. It works!

Conclusion

It’s easy to come up with a normalized relational database schema for a simple tenant-project-issue data model with a fixed set of fields. We can even make it efficient for large collections of issues by using KeySet pagination, being extremely careful to create the right indexes, and limiting the ways in which our Grid View can sort and group data.

If your PM insists on a richer set of functionality, you could consider a hybrid strategy of incrementally loading data into the client using some choice of fixed orders and then doing everything client side once all the data has loaded. For really big datasets, you need a design that lets you identify and load a subset of interest. For example, allowing the user to organize huge projects as multiple sub-projects.

Hold on, the PM has just turned up. They’re OK with single column sorting. What they really want is the ability to add custom fields to issues. Yes, the custom fields need to appear in the Grid View. Of course you need to be able to sort on them too.

We’ll get started on that next time.