When we aggresively denormalized our Grid View relational database, we were able to achieve our aim of a single table solution. However, it came with a lot of unintended consequences. In order to support up to 100 custom fields of each type, we added 400 custom field columns to our issue table, most of which were NULL. In theory the overhead should have been minimal. In practice, we ran into all kinds of implementation and operational problems.

Recently1, relational databases have added support for JSON columns. There’s even an ISO standard for it. Unfortunately, implementations vary wildly in their standards conformance and reliance on non-standard extensions. Fortunately, Postgres has a mature and conformant implementation.

We’ve replaced the four hundred typed, mostly NULL, custom field columns with a single JSON column.

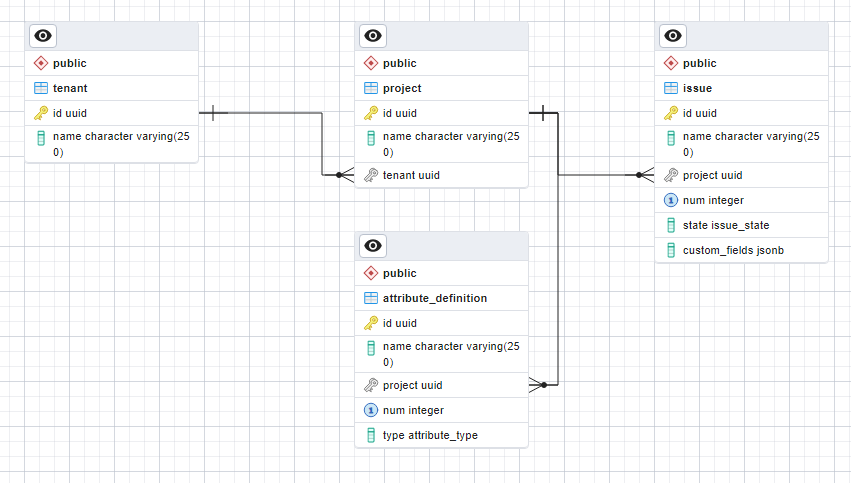

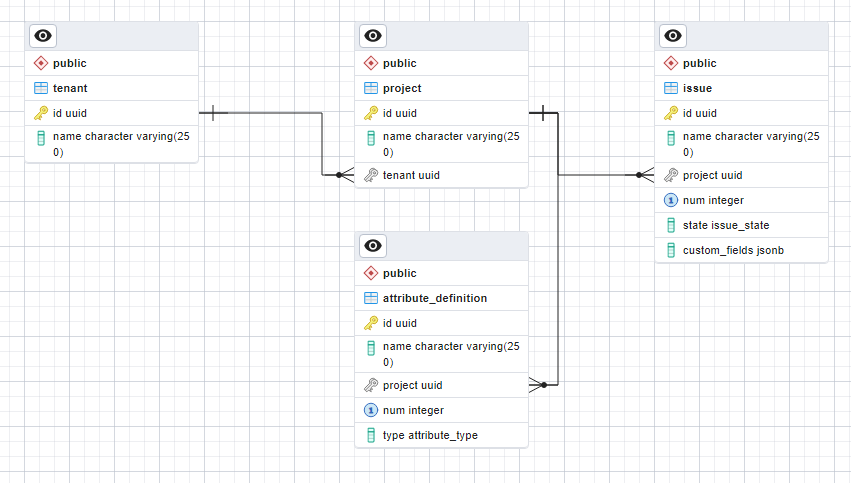

Schema

The most straight forward schema is to use a JSON document with attribute definition ids as keys, and custom field values as values. Here’s what our sample data would look like.

| id | name | project | num | state | custom_fields |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 020e | Needs Painting | 35e9 | 1 | open | {“3812”:”2023-05-01”,”882a”:”2023-06-01”} |

| 3544 | Launch new newspaper! | 7b7e | 1 | closed | |

| 67d1 | Check for rust | 35e9 | 2 | closed | {“3812”:”2023-05-02”,”882a”:”2023-06-02”} |

| 83a4 | Hire reporter for showbiz desk | 7b7e | 2 | open | |

| af34 | Girder needs replacing | 35e9 | 3 | open | {“3fe6”:42,”47e5”:”Approved”} |

JSON Storage Format

Postgres has two JSON storage types. The JSON type stores the JSON document as a string with whitespace, ordering and numeric formatting preserved. The JSONB type converts the JSON document into a binary representation optimized for fast query and indexing.

The JSON type has 4 bytes of document structure overhead per custom field (double quotes, colon, comma), plus another 3-6 per document (curly brackets, string length2). Then we need to add 32 bytes for the attribute id UUID encoded as a string. Finally, each value has potential overhead from the way it’s encoded in JSON.

| Custom Field Type | JSON Encoding | Storage Overhead (worst case) |

|---|---|---|

| Date3 | ISO formatted string “YYYY-MM-DD” | 8 |

| Integer4 | JSON number | 7 |

| Double5 | JSON number | 10 |

| Text6 | JSON string | 1 |

The JSONB type7 has 8 bytes of document structure overhead per custom field, plus another 8 per document. Keys are encoded as strings, so we still need 32 bytes for the attribute id UUID. However, value type overhead is less.

| Custom Field Type | JSONB Encoding | Storage Overhead (worst case) |

|---|---|---|

| Date8 | ISO formatted string YYYY-MM-DD | 6 |

| Integer9 | Numeric | 5 |

| Double9 | Numeric | 7 |

| Text10 | String | 0 |

How does the storage overhead compare with our previous implementation attempts? In the table below I use the average of the worst case storage overhead for each value type: 6.5 bytes for JSON, 4.5 for JSONB.

| Custom Fields Used | Combined table | Attribute Value table | JSON | JSONB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 50 | 0 | 1 | 8 |

| 1 | 50 | 56 | 49 | 53 |

| 2 | 50 | 112 | 91 | 97 |

| 3 | 50 | 168 | 134 | 142 |

Storage overhead doesn’t look great compared with our combined table with lots of columns. It’s also only marginally better than our current best in class implementation with a separate attribute value child table.

Access Patterns

As always, the key query is retrieving issues on a project. We can retrieve the data as stored, with the custom fields encoded using JSON, and parse the JSON in our app server.

SELECT id,name,num,state,custom_fields

FROM issue WHERE issue.project = '35e9' ORDER BY num DESC;

Or we can get the database to extract the values for us. JSONB format is recommended if you’re doing anything more than just storing and retrieving JSON documents.

SELECT id,name,num,state,

to_date(custom_fields->>'3812','YYYY-MM-DD') AS custom1,

to_date(custom_fields->>'882a','YYYY-MM-DD') AS custom2,

(custom_fields->'3fe6')::int4 AS custom3,

custom_fields->>'47e5' AS custom4

FROM issue WHERE issue.project = '35e9' ORDER BY num DESC;

The -> operator extracts the value for the specified top level key. The value returned is in JSONB format, so needs to be cast to the appropriate type. The ->> operator is a convenience which extracts the value and casts to text type.

We can sort by custom field easily enough, complete with a secondary sort on num to support pagination.

SELECT id,name,num,state,

to_date(custom_fields->>'3812','YYYY-MM-DD') AS custom1,

to_date(custom_fields->>'882a','YYYY-MM-DD') AS custom2,

(custom_fields->'3fe6')::int4 AS custom3,

custom_fields->>'47e5' AS custom4

FROM issue WHERE issue.project = '35e9' ORDER BY custom1, num;

Of course, we don’t have any index to support this query. The best the query planner can do is use the (project,state,num) index to retrieve all the issues for the project and then sort them.

Sort (cost=8.18..8.18 rows=1 width=584)

Sort Key: (to_date((custom_fields ->> '3812'::text), 'YYYY-MM-DD'::text)), num

-> Index Scan using issue_project_state_num_idx on issue (cost=0.13..8.17 rows=1 width=584)

Index Cond: (project = '35e9'::uuid)

Note that because my query is ordered by the output column custom1, the sort has to convert the text extracted from JSON to a Postgres date. The string encoding used for date sorts in date order, so it would be more efficient to order by custom_fields->>'3812' and save the cost of the conversion on every comparison. When using JSON with Postgres, you will spend a lot of time thinking about type conversions.

Does Postgres have some kind of special JSON index?

Postgres GIN Index

As a matter of fact it does. A GIN index can be used to “efficiently search for keys or key/value pairs occurring within a large number of JSONB documents”. It sounds like magic. Define one index on our custom_fields JSON column and all the keys and values contained will be indexed.

CREATE INDEX idx_custom_fields ON issue USING GIN (custom_fields);

Let’s try it out. I’ve adjusted the query to order by the JSON value directly, without the type conversion.

SELECT id,name,num,state,

to_date(custom_fields->>'3812','YYYY-MM-DD') AS custom1,

to_date(custom_fields->>'882a','YYYY-MM-DD') AS custom2,

(custom_fields->'3fe6')::int4 AS custom3,

custom_fields->>'47e5' AS custom4

FROM issue WHERE issue.project = '35e9' ORDER BY custom_fields->>'3812', num;

And check the query plan again …

Sort (cost=8.18..8.18 rows=1 width=584)

Sort Key: ((custom_fields ->> '3812'::text), num)

-> Index Scan using issue_project_state_num_idx on issue (cost=0.13..8.17 rows=1 width=584)

Index Cond: (project = '35e9'::uuid)

Oh dear. The GIN index wasn’t used. The problem is that project is a regular column, not a JSON key. Luckily, attribute definitions are per project. We can query for issues with the required attribute defined. That will mean we have to go back to two separate queries to paginate over all the data: one for issues with the attribute defined (using the GIN index) and one for issues without (using the original project index).

The second query works as we’d expect, using the existing (project,num) index to iterate over issues on the project in num order, with a filter condition that ignores issues that don’t have the custom field defined.

EXPLAIN SELECT id,name,num,state,

to_date(custom_fields->>'3812','YYYY-MM-DD') AS custom1,

to_date(custom_fields->>'882a','YYYY-MM-DD') AS custom2,

(custom_fields->'3fe6')::int4 AS custom3,

custom_fields->>'47e5' AS custom4

FROM issue WHERE issue.project = '35e9' AND NOT custom_fields ? '3812' ORDER BY num;

Index Scan using issue_project_num_key on issue (cost=0.13..8.17 rows=1 width=584)

Index Cond: (project = '35e9b60a-d4d0-47ce-b9bd-af0a961ea65c'::uuid)

Filter: (NOT (custom_fields ? 'd1'::text))

How does the GIN index get on with the first query?

EXPLAIN SELECT id,name,num,state,

to_date(custom_fields->>'3812','YYYY-MM-DD') AS custom1,

to_date(custom_fields->>'882a','YYYY-MM-DD') AS custom2,

(custom_fields->'3fe6')::int4 AS custom3,

custom_fields->>'47e5' AS custom4

FROM issue WHERE custom_fields ? '3812' ORDER BY custom1;

Sort (cost=12.04..12.05 rows=1 width=584)

Sort Key: ((custom_fields ->> '3812'::text))

-> Bitmap Heap Scan on issue (cost=8.00..12.03 rows=1 width=584)

Recheck Cond: (custom_fields ? '3812'::text)

-> Bitmap Index Scan on idx_custom_fields (cost=0.00..8.00 rows=1 width=0)

Index Cond: (custom_fields ? '3812'::text)

Well, it is being used to find issues with the required custom field defined (the ? operator checks whether a top level key exists). However, we’re still fetching all the issues and then sorting them. What’s going on?

GIN indexes are not sorted. They operate in the same way as a search index, mapping search terms (for JSON, that’s keys and values) to posting lists of rows that contain them. A GIN index can only be used to test for existence and equality. The database still has to sort the matching issues.

If you look at the query plan, you’ll see that the index lookup uses two phases. In the initial “Bitmap Index Scan” phase, the index is used to identify all database pages with rows that contain the search terms. The index doesn’t contain enough information to definitively evaluate the query condition. The second “Bitmap Heap Scan” phase loads each identified page in turn and evaluates the query condition on each row in the page.

Is that it for JSON? Not quite. There is a way to build normal sorted indexes that combine both regular columns and JSON keys. However, before we can do that, we need to change our JSON schema.

Compact Schema

The current schema has two problems. First, the UUID attribute keys make for particularly verbose JSON. Second, having different JSON keys for every project makes it impractical to define indexes that cover them all.

We can solve both problems with an extra level of indirection. Give each of the 400 possible custom field “slots” a short id to use as a JSON key. We can encode custom field type and number in a two character string11. Add a json_key column to the attribute definition table which specifies which JSON key that attribute is using.

| id | name | project | num | state | custom_fields |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 020e | Needs Painting | 35e9 | 1 | open | {“d1”:”2023-05-01”,”d2”:”2023-06-01”} |

| 3544 | Launch new newspaper! | 7b7e | 1 | closed | |

| 67d1 | Check for rust | 35e9 | 2 | closed | {“d1”:”2023-05-02”,”d2”:”2023-06-02”} |

| 83a4 | Hire reporter for showbiz desk | 7b7e | 2 | open | |

| af34 | Girder needs replacing | 35e9 | 3 | open | {“i1”:42,”t1”:”Approved”} |

with a corresponding attribute definition table

| id | name | project | num | type | json_key |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3812 | Start | 35e9 | 1 | date | d1 |

| 882a | End | 35e9 | 2 | date | d2 |

| 3fe6 | Num Items | 35e9 | 1 | int | i1 |

| 47e5 | Sign Off | 35e9 | 2 | text | t1 |

What does that do to the overhead?

| Custom Fields Used | Combined table | Attribute Value table | JSON | JSONB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 50 | 0 | 1 | 8 |

| 1 | 50 | 56 | 19 | 23 |

| 2 | 50 | 112 | 31 | 37 |

| 3 | 50 | 168 | 44 | 52 |

Looking much healthier. Here’s the query we want to support again.

SELECT id,name,num,state,

to_date(custom_fields->>'d1','YYYY-MM-DD') AS custom1,

to_date(custom_fields->>'d2','YYYY-MM-DD') AS custom2,

(custom_fields->'i1')::int4 AS custom3,

custom_fields->>'t1' AS custom4

FROM issue WHERE issue.project = '35e9' ORDER BY custom_fields->>'d1', num;

Now, how do we index it?

Postgres Expression Index

Postgres has a wonderful feature which allows you to define indexes on expressions. That is, any function or scalar expression computed from one or more columns in the table.

In our case, we need an index on project, the ‘d1’ JSON key and num.

CREATE INDEX idx_project_d1_num ON issue (project, custom_fields->>'d1', num);

Now let’s look at the query plan.

Index Scan using idx_project_d1_num on issue (cost=0.13..8.17 rows=1 width=616)

Index Cond: (project = '35e9b60a-d4d0-47ce-b9bd-af0a961ea65c'::uuid)

Success! We can build any indexes we want over any combination of columns and JSON keys.

An expression index is more expensive to maintain than a regular index, as the expressions need to be re-evaluated and the index updated on any change to the columns used in the expression.

This index on a JSON date is also larger than one created on a real date column. In theory, we could convert the JSON string to a date before indexing, improving index size and read performance at the cost of additional write time cost. In practice, Postgres refused to create the index because the date conversion function is not marked IMMUTABLE. This is a known issue as date conversion may depend on the current locale.

I was able to create indexes for integer and double custom fields using native types.

CREATE INDEX idx_project_i1_num ON issue (project, ((custom_fields->'i1')::int4),num);

CREATE INDEX idx_project_f1_num ON issue (project, ((custom_fields->'f1')::float8),num);

You need to take great care when querying using an expression index. Your query expression needs to exactly match the expression used to create the index, otherwise the index won’t be used.

Conclusion

Those of you that have been following along with this series, will realize that we’ve ended up with exactly the same indexing strategy as the aggresively denormalized combined table we started with. If we want to be able to sort on any of our 400 possible custom fields, we will need 400 indexes. To keep index management under control we will have to use partial indexes and only index issues which have that custom field defined. Which in turn means we’re back to paginating over two separate queries when sorting by custom field.

What have we gained? We got to play with the cool JSON feature in Postgres. We replaced the 400 mostly NULL columns we previously used to store custom fields with a single JSONB column. We’re using less storage space than the combined table for issues with two or fewer custom fields.

On the downside

- Any change to a custom field requires a read/modify/write of the containing JSON document

- We will end up using a lot more storage space than the aggressively denormalized solution for issues with three or more custom fields

- Our four hundred indexes are more expensive to maintain

- The indexes are larger, unless you’re prepared for more complexity and write time cost by converting data types before indexing

- We have to deal with the added complexity of type conversion in our queries

- JSON is still a relatively new feature in the relational database world. We will have operational difficulties with tooling that doesn’t support JSONB columns. The data warehouse team will still hate us.

There are clearly compromises involved when shoehorning JSON support into a mature technology like a relational database. Maybe things will work more smoothly with a purpose built NoSQL JSON database?

Next time, we’ll take a look at MongoDB.

Footnotes

-

Within the last 10 years. Which is recent when you consider the development history of relational databases. ↩

-

Variable length data, like strings, is encoded using either a 1 byte varlena header (up to 126 bytes long) or a 4 byte varlena header (up to 1G long). ↩

-

ISO formatted string is 10 characters long enclosed in double quotes, compared with 4 byte binary representation in normal Postgres column ↩

-

Integer formatted as string is between 1 and 11 characters long, compared with 4 byte binary representation in normal Postgres column ↩

-

Double formatted as string is between 1 and 18 characters long, compared with 8 byte binary representation in normal Postgres column ↩

-

String is enclosed in double quotes in JSON format, compared with a 1-4 byte header followed by characters in normal Postgres column ↩

-

I couldn’t find any formal spec for JSONB so had to rely on the source code and an overview blog article to understand the format. ↩

-

No special date encoding, still ISO formatted string. No double quotes needed in JSONB document structure. ↩

-

JSON numbers (both integer and double) are stored using the Postgres arbitrary precision Numeric type. This uses a base 10000 encoding (each group of 4 decimal digits is stored as an int16) with 2 byte Numeric header and a 1 byte varlena header. Integers need at most 3 int16 digits, doubles at most 6. ↩ ↩2

-

No double quotes needed in JSONB document structure. ↩

-

To keep the examples readable, I’m using letter (for type) + number, which would need up to 3 characters. As we have at most 400 custom fields per project, you could easily come up with a two character encoding. For example, using base 64. ↩