We’ve been good. We’ve followed the rules. Our database is fully normalized and we have all the referential integrity checks we need in place. And yet. Our queries seem overly complex. There’s a constant battle to try and keep queries scalable. Despite all that, performance is not what we’d like.

Maybe we could try denormalizing the database? Denormalization attempts to improve read performance by adding redundant copies of data. It comes at the cost of reduced write performance and often with a loss of referential integrity.

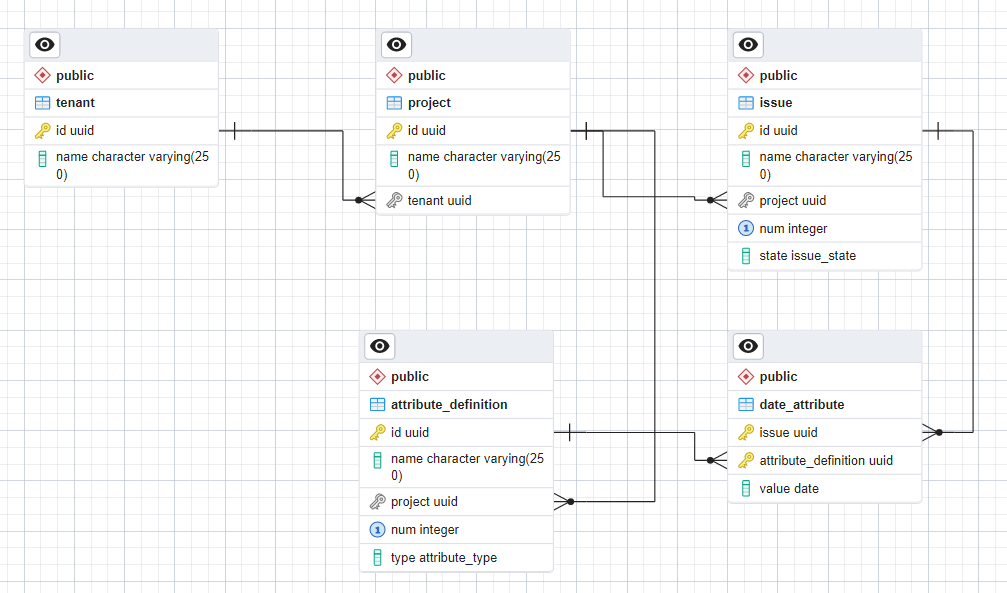

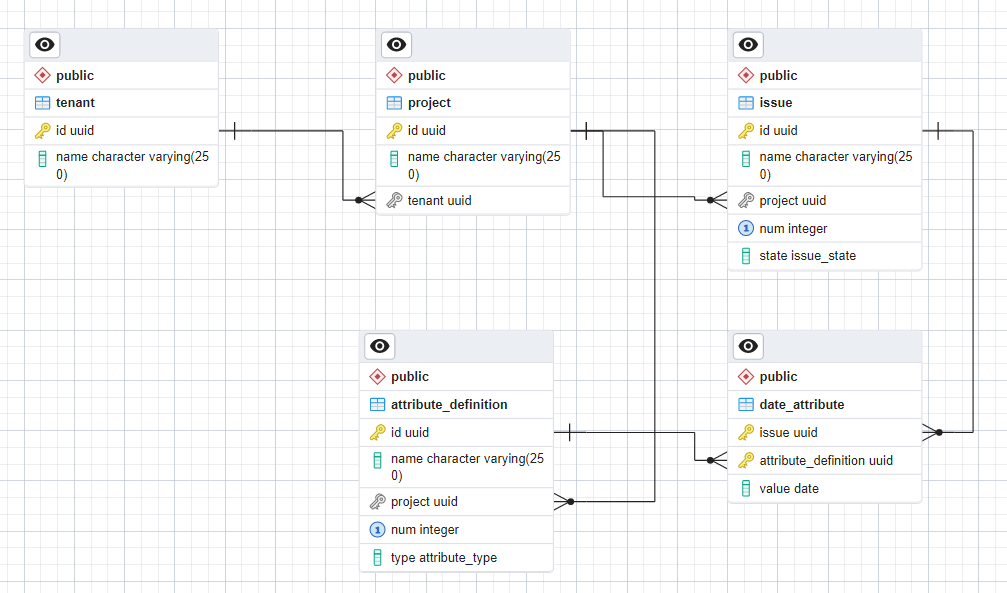

Last time I left you with a list of problems inherent in our normalized database design for a Grid View with support for custom fields.

- We achieved O(nlogn) scaling at the cost of a really big constant factor due to the number of joins required.

- All those joins make the queries complex. As do the per custom field clauses in each query. Even worse, you have to dynamically build the queries at run time because every project has different numbers and types of attributes.

- You need an extra join for each attribute type.

- Sorting on a custom field requires complex pagination code that works across two different queries, one of which can have problems with long query times.

- The secondary sort for duplicate custom field values is on issue id, which to an end user looks like a random order.

We’re going to look at some different ways of denormalizing our database schema, see what the pros and cons are, and whether they address any of our pain points.

Indexes

You can attempt to improve read performance of a normalized relational database by adding an index. The index contains redundant copies of the data stored in the source table. Maintaining the index comes at the cost of reduced write performance. Sound familiar?

Adding indexes has many of the same trade offs as denormalizing a database. The difference is that the database handles all the details for you. It’s responsible for keeping the indexes in sync as you make changes to your tables.

If you can achieve what you want using an index, rather than by manually denormalizing, then do so. The downside of relational database indexes is that they’re defined per table. Unless you have a table containing all the data you’re interested in, you can’t use an index to organize it.

Materialized Views

A materialized view is a database object that contains the results of a query. Once created, you can query it like a table and even build indexes for it.

The foundation for our problematic queries is a complex join that combines the issue and per type attribute value tables for a project. Going back to our sample data set, it combines the issues for the engineering project

| id | name | project | num | state |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 020e | Needs Painting | 35e9 | 1 | open |

| 67d1 | Check for rust | 35e9 | 2 | closed |

| af34 | Girder needs replacing | 35e9 | 3 | open |

with the attribute values for each issue

| issue | attribute_definition | value |

|---|---|---|

| 020e | 3812 | 2023-05-01 |

| 020e | 882a | 2023-06-01 |

| 67d1 | 3812 | 2023-05-02 |

| 67d1 | 882a | 2023-06-02 |

resulting in

| id | name | project | num | state | custom1 | custom2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 020e | Needs Painting | 35e9 | 1 | open | 2023-05-01 | 2023-06-01 |

| 67d1 | Check for rust | 35e9 | 2 | closed | 2023-05-02 | 2023-06-02 |

| af34 | Girder needs replacing | 35e9 | 3 | open |

If we had a materialized view for these results it would be simple to query and simple to build indexes for. However, in most1 relational databases (Postgres included), materialized views are a snapshot at a point in time. They aren’t automatically updated as the source tables change. You have to explicitly refresh them. The usual implementation is to drop the old results, rerun the query from scratch and save the new results. It’s simply not practical to refresh a materialized view on every change to the source data.

Per Project Tables

Instead of messing around with materialized views, why don’t we directly create tables in the format we want? Every project is different, so we would need a separate issue table per project.

In theory this is workable. The total amount of data is the same whether stored in a couple of big tables or lots of smaller per project ones. There is a hard limit on the number of tables, but you’ll end up having to shard your database long before you hit it. Postgres, for example, has a limit of around 1431 million relations (which includes tables, indexes, and views).

If you try this, you run into an interesting selection of practical problems. Databases are not designed or tested to operate with millions of tables. Normal use is tens or hundreds of tables.

- Database implementations typically use one or more dedicated files per table. It’s common to run into filesystem limitations such as open file and inode limits.

- There is usually a significant amount of per table storage overhead. You will need much more disk space for lots of small tables than a few big ones.

- There are many internal database operations that are O(n) in the number of tables. For example, you may find a significant increase in the time it takes for the query planner to evaluate a query.

- Database administration tooling is built with typical cases in mind. For example, the Postgres pgAdmin graphical administration tool is built to display a list of all your tables for you to interact with. The GUI isn’t designed to scale to thousands let alone millions of tables.

- Lots of tooling assumes that the set of tables is largely static, changing only when there’s a significant change to the application. It’s not designed for a situation where you may be creating tens of tables a day.

- Typical day to day operations become impractical to perform manually. Your development team will need to build their own custom automated tooling.

- Expect lots of friction with other teams that might have to interact with your database. For example, the security and compliance teams will have a hard time reviewing your schema. The data warehouse team will pull their hair out trying to figure out how to ingest data from your system.

The only team I know that tried this approach, abandoned it in the end because of the ongoing practical difficulties.

Combined Attribute Value table

Maybe we should start with a simpler change and try and bank a small win? Can we get rid of separate attribute value tables for each type of attribute value?

We could have a single table for all attribute values with a separate column for each type. Each row would use the appropriate column to store the value with the others set to NULL. Our sample data would look something like this once we’ve added a couple of new attribute definitions.

| issue | attribute_definition | date_value | integer_value | double_value | text_value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 020e | 3812 | 2023-05-01 | |||

| 020e | 882a | 2023-06-01 | |||

| 67d1 | 3812 | 2023-05-02 | |||

| 67d1 | 882a | 2023-06-02 | |||

| af34 | 3fe6 | 42 | |||

| af34 | 47e5 | Approved |

We end up with simpler queries with a fixed number of joins (3 in the worst case). All attribute values are sorted together in the same table, so a single O(logn) query can return all the values for an issue.

SELECT id,name,num,state,custom1,custom2,custom3,custom4 FROM issue LEFT JOIN (

SELECT issue,

MAX(CASE WHEN attribute_definition='3812' THEN date_value END) custom1,

MAX(CASE WHEN attribute_definition='882a' THEN date_value END) custom2,

MAX(CASE WHEN attribute_definition='3fe6' THEN integer_value END) custom3,

MAX(CASE WHEN attribute_definition='47e5' THEN text_value END) custom4

FROM attribute GROUP BY issue)

AS attribs ON id = attribs.issue

WHERE issue.project = '35e9' ORDER BY num DESC;

resulting in

| id | name | num | state | custom1 | custom2 | custom3 | custom4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| af34 | Girder needs replacing | 3 | open | 42 | Approved | ||

| 67d1 | Check for rust | 2 | closed | 2023-05-02 | 2023-06-02 | ||

| 020e | Needs Painting | 1 | open | 2023-05-01 | 2023-06-01 |

On the downside, this is clearly not in normal form. Each specific value for attribute_definition has NULL values for the same set of columns. We are storing redundant data. However, NULL values are cheap. In Postgres each row of this table needs one additional byte of storage compared to a row in a dedicated per type attribute value table.

The other problem with storing redundant data is keeping everything in sync. However, that’s not a problem here. The unused columns are set to NULL when an attribute value row is created. They never change after that. Only the used value column changes when a custom field is edited. It’s as easy as it gets for application code to keep this consistent.

This denormalization is a clear win. So much so, that every otherwise normalized system I’ve come across uses it.

Combined Issue and Attribute Value table

So far, we managed to address one of our list of issues. We got rid of the extra join per attribute type. And we found out how cheap NULLs are. Can we use that to combine the issue and attribute value tables? Something like :

| id | name | project | num | state | date1 | date2 | date3 | … | int1 | int2 | int3 | … | dbl1 | dbl2 | dbl3 | … | txt1 | txt2 | txt3 | … |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 020e | Needs Painting | 35e9 | 1 | open | 2023-05-01 | 2023-06-01 | ||||||||||||||

| 3544 | Launch new newspaper! | 7b7e | 1 | closed | ||||||||||||||||

| 67d1 | Check for rust | 35e9 | 2 | closed | 2023-05-02 | 2023-06-02 | ||||||||||||||

| 83a4 | Hire reporter for showbiz desk | 7b7e | 2 | open | ||||||||||||||||

| af34 | Girder needs replacing | 35e9 | 3 | open | 42 | Approved |

with an attribute definition table which specifies which column is used to store that definition’s value :

| id | name | project | num | type | column |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3812 | Start | 35e9 | 1 | date | date1 |

| 882a | End | 35e9 | 2 | date | date2 |

| 3fe6 | Num Items | 35e9 | 3 | int | int1 |

| 47e5 | Sign Off | 35e9 | 4 | text | txt1 |

Queries are simple without a join in sight :

SELECT id,name,num,state,

date1 AS custom1,

date2 AS custom2,

int1 AS custom3,

txt1 AS custom4

FROM issue WHERE issue.project = '35e9' ORDER BY num DESC;

The same query structure works for both fixed and custom fields. You still need to dynamically generate the query but its a much simpler process than before. You have complete flexibility on how you index the data. For example, you can finally create an index that let’s you sort by custom field value and then by num. Pagination is simple and efficient for both fixed and custom fields.

That all sounds great. What’s the catch?

Look at the sample issue table above. Scroll all the way across. That’s an awful lot of columns. Don’t we need to support 100 custom fields of each type? That means we’re adding 400 columns, most of which store NULLs. What sort of overhead are we adding?

Postgres has a limit of 1600 columns, so we’re comfortably inside that. It uses one extra bit per row to specify whether a column is NULL or has an actual value. So, adding 400 NULL columns needs an extra 50 bytes per row.

How does this compare with the separate attribute value table? Clearly worse for issues that have no custom field values. However, the balance changes once we add a single custom field value. The attribute value table has an overhead (storage used for everything apart from the custom field value) of 56 bytes. The postgres row header uses 24 bytes and then you need 16 bytes for each of the issue id and the attribute definition id.

| Custom Fields Used | Combined table overhead | Attribute Value table overhead |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 50 | 0 |

| 1 | 50 | 56 |

| 2 | 50 | 112 |

| 3 | 50 | 168 |

If the PM insists that we need to support 100 custom fields of each type, I think it’s reasonable to expect that we’ll average at least one custom field per issue. If we get anywhere near a hundred, we’re saving a lot of space.

What about the indexes? If we need to support sort on every custom field, then we’ll need 400 indexes. An index on (project,value,num) will use 96 bytes per row. Now the overhead looks like

| Custom Fields Used | Combined table overhead | Attribute Value table overhead |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 38450 | 0 |

| 1 | 38450 | 152 |

| 2 | 38450 | 304 |

| 3 | 38450 | 456 |

Ouch. That’s an awful lot of NULLs we’re indexing. On top of the storage cost, creating a new issue will involve updating 400 indexes. That’s really trading off write performance for read performance.

Can we avoid indexing the NULLs? Postgres supports partial indexes which let you specify which rows should be included. If we only index custom fields that are used, we’ll end up with the same number of index rows in both cases.

| Custom Fields Used | Combined table overhead | Attribute Value table overhead |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 50 | 0 |

| 1 | 146 | 152 |

| 2 | 242 | 304 |

| 3 | 338 | 456 |

Phew. We’re winning again. Unfortunately, we’re now back to paginating over two different queries when sorting by custom field.

Time to take stock. From our original list of problems we’ve fixed 1, 3 and 5. We’ve made some progress on 2 but still need to dynamically generate queries per project. Problem 4 remains the same.

Is it worth it? One team I worked with thought so after extensive prototyping. However, after a couple of years in production, they decided to switch to a separate attribute value table. As with per project tables, it was practical problems that ground them down.

- There are many database internal operations that are O(n) in the number of columns. For example, to read a column value from a row, the database has to first analyze the bitmask of NULL columns to work out where the value is stored.

- There are many database internal operations that are O(n) in the number of indexes. The query planner, for example, will iterate over every index and laboriously test each one to see if it’s applicable to the current query2.

- There was standard tooling that they wanted to use that couldn’t cope with that number of columns or that number of indexes. For example, it was standard practice to use AWS DMS to replicate data into our data warehouse. The DMS task for this table took forever to complete and frequently failed.

- Day to day operational management of this database was significantly more challenging than for other databases of a similar size.

- There was lots of friction with other teams that needed to interact with the database.

Dropping Referential Integrity Constraints

A consequence of denormalizing a database is that application code takes on more responsibility for ensuring integrity and consistency of the data. Once you take a step down that road, it can be tempting to look for other “simplifications”.

Write performance has reduced because of the redundant data we need to keep up to date. Maybe we can get some of that back by getting rid of database level constraints? After all, our application code is designed to keep everything consistent. Why waste performance having the database check up on us?

In my experience, any team that can make this argument is not self aware enough to realize that they can’t write 100% bug free code. Which in turn means they don’t realize that they need to monitor the database for the inevitable inconsistencies that will arise and have a process for fixing them.

Perhaps you’ve decided to drop the foreign key constraint that ensures an issue always has a valid project id. Maybe your concern is performance, maybe you’re trying to do some complex operation where the constraints are temporarily violated. Doesn’t matter. The important thing is to realize that you will, at some point, end up with issues in the database with a junk or missing project id.

This is a serious problem for a multi-tenant application. You are managing data on behalf of multiple customers. At the very minimum, you need to keep track of what data belongs to what customer. In many jurisdictions, customers have a legal right to a copy of all their data or to have it deleted on request.

If you have issues with a junk or missing project id, you have no way of knowing which customer owns them. Our schema relies on consistent relationships between issue, project and tenant to determine the tenant id that owns each issue. If you remove the constraint, you need to find another way of ensuring we can’t lose track of which customer owns each issue.

Ironically, a common way of doing this is to further denormalize the database. If it’s important that we keep track of who owns every significant row of data, then ensure that every significant row of data has a tenant id column. If every row of data is tagged with a tenant id, it doesn’t matter how screwed up referential integrity gets. We can always3 identify the owner.

Conclusion

The traditional recommendation is to start with a normalized relational database design and very carefully introduce the minimum amount of denormalization needed to meet your goals (ideally none). I think that’s sound advice.

Relational databases are amazing pieces of technology. There’s a temptation to find new and creative ways of using them that stray far from the confines of normalized design. Unfortunately, when you’re way out on the cutting edge you’re going to run into all kinds of practical difficulties that are hard to forsee when you start the journey.

All very philosophical, but we haven’t got much further with addressing our list of problems. Maybe where we went wrong is trying to use a relational database for this? We’re trying to model issues with per project custom fields using a database with fixed schemas. Wouldn’t it be simpler if each issue could include just the attributes it needs?

I think it’s time to take a look at NoSQL databases. Before we do that, relational databases have one last card to play. Spurred on by the success of the NoSQL movement, they started to add support for JSON columns. Fed up with the straitjacket of a schema? Store whatever you want as a blob of JSON.

Next time we’ll see if storing custom fields as JSON can solve all our problems.

Footnotes

-

SQL server supports indexed views which do automatically update. However, it only supports simple queries. In particular left joins and joins with sub queries are not allowed, so no use in our case. ↩

-

See the last example in the Postgres documentation on partial indexes. ↩

-

You also need to ensure that tenant ids can’t be reused (another reason for using UUIDs) and that you have a permanent record somewhere that maps tenant ids to customer information. You might use soft deletes on the tenants table or have a persistent log of all changes or store that mapping somewhere else. Or all three. ↩