Many of us first became aware of the risks of a supply-chain attack with the SolarWinds hack of 2020. Attackers compromised the build system belonging to SolarWinds, the creator of popular network monitoring tool Orion.

Malware was installed on the build system. When it detected that an Orion build was in progress, it replaced one of the built DLLs with a clone containing a backdoor. Any SolarWinds customer that applied the Orion update was compromised in turn. Customers included high profile targets like the US Government, Microsoft, other software and hardware suppliers, together with many security firms.

At the time, many in the open source world claimed that this kind of attack was inherent to proprietary software. The transparency of open source software made it more secure. The open source principle of bringing many eyeballs meant that more errors would be found and attacks prevented.

Hopefully this year’s XZ supply chain attack will be a wake up call. XZ Utils is the perfect example of a foundational project thanklessly maintained by some random person for the last twenty years. In this case, that person is Lasse Collin. Lasse Collin was subjected to a social engineering campaign aimed at getting him to take on another maintainer. As it happened, a newly active contributor called Jia Tan was willing to step up.

XZ Utils

XZ Utils is a lossless compression utility and associated library that has been adopted by most Linux distributions. Jia Tan compromised XZ’s liblzma library. On many systems, liblzma is a dependency of a dependency of the SSH secure login utility. When the compromised library is loaded into an SSH process, it hooks itself into SSH’s authentication routines to enable a backdoor.

How did Jia Tan get past the scrutiny of so many eyeballs? Just like with SolarWinds, they compromised the build process. Only in this case, it was much easier.

Open source projects use a variety of tool stacks to build and make available releases of their software. The general principle is the same. The source code is retrieved from a public repository, it gets built and packaged up, then the package is posted in some form of public registry where potential consumers can find and download it. Often the maintainer will sign the package to ensure that it can’t be tampered with later.

As a consumer you have to trust the project maintainer when they say that the package they posted to the public registry corresponds to the source code that the many eyeballs have reviewed. It’s not practical to review compiled binary code. Even packages for scripting languages like JavaScript are unreadable once they’ve been minified and bundled.

All Jia Tan had to do was modify their local copy of the source code before building and releasing it. They took some care to avoid raising suspicions. They made sure the resulting package size was comparable to the original build. They disguised the payload as a binary test file. The only file they modified compared to the original source code was the installation script. Even so, it’s trivial compared with the SolarWinds attack.

Dependency Management

Open source promotes sharing and reuse of software. That’s a good thing. However, it does mean that all open source software relies on a huge stack of nested dependencies. I’m working on a modest open source project. It’s a front-end NPM package based on React. React is the only immediate runtime dependency. My project uses a standard set of tooling.

Altogether, you need nearly 1000 dependencies to build and run.

You might be able to validate and trust the maintainers of your immediate dependencies. It’s not practical to do the same for every dependency in the stack. You have to rely on the many eyeballs principle. Which has this gaping hole between what you can see in the source code repo and what ends up in the package you consume.

If you’re sensibly paranoid, you’ll stick to consuming source code. Forgo the convenience of package managers. However, if the secure option is too much effort, most people won’t bother. A thousand dependencies? I’m sure it will be fine.

Sigstore

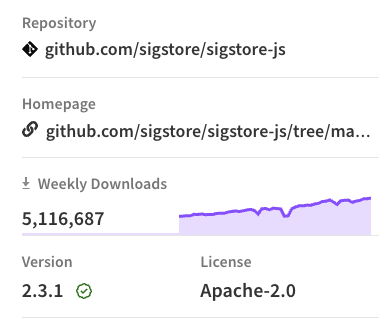

Sigstore is an open source effort to improve supply chain security. It focuses on providing an easy, standardized way for maintainers to sign their packages so that developers can easily verify that the packages they consume have not been tampered with since they were created.

Sigstore abstracts away the need for maintainers and developers to manage signing keys. Signatures are created using ephemeral signing keys associated with an OpenId Connect identity. Package consumers can verify package integrity and directly determine the publisher’s identity, without having to work out how to obtain the correct public key. All signing events are recorded in a tamper-resistant public log so developers can audit signatures.

Which sounds good but still seems like a lot of work for maintainers and developers. It also does nothing to address the gap between source code repo and signed package.

NPM Provenance

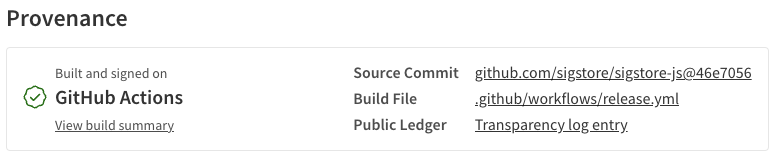

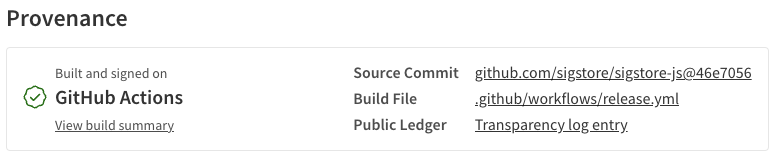

Last year GitHub announced a new provenance feature for NPM packages that uses sigstore. Packages can include a provenance statement that ties a built package to a specific source code repo and commit. The feature is integrated with GitHub actions. All you have to do is configure your GitHub actions workflow correctly by adding a couple of flags.

Packages with provenance are identified as such on the NPM registry with links to the corresponding commit and build process.

Which sounds great. It makes it easy for maintainers to publish packages with provenance and really easy for developers to see whether a package has full source-to-package integrity. However, don’t we still have the problem of having to trust the maintainers of every dependency?

Which is where the really clever bit comes in. The packages aren’t signed by the maintainers. They’re signed by a trusted CI/CD system. At time of writing the only trusted CI/CD systems are GitHub Actions and GitLab CI/CD. The package has to be built using a cloud-hosted runner managed by the CI/CD system, with a build workflow defined in the source code repo.

Consumers have full transparency of how the package was built. The many eyeballs principle works properly again. Instead of navigating a thousand trust relationships there’s only one.

Adoption

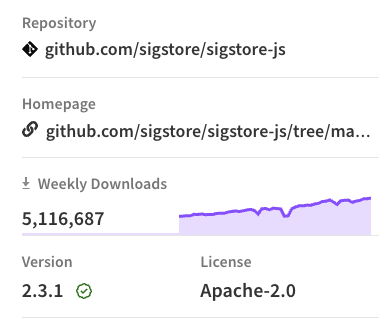

It’s now just over a year since the NPM provenance feature was released. Is it making a difference?

NPM Registry

The integration into the NPM registry is pretty minimal. As well as the provenance statement visible only if you scroll right down to the bottom of the package page, there’s a subtle check mark next to the package version.

That’s it. There’s no integration into package search yet. You can’t filter packages to only show those with provenance. You can’t even see the provenance checkmark in the search results. You have to go to each package’s page and check there.

NPM Client

The NPM client also has some minimal support. There’s a new npm audit signatures command which will tell you how many packages have provenance statements and whether any have been tampered with.

% npm audit signatures

audited 971 packages in 9s

971 packages have verified registry signatures

101 packages have verified attestations

However, there’s no way to list which packages are missing provenance (aka “verified attestations” ). In my own project, just over 10% of the packages I use have provenance. There’s still a long way to go.

Call to Arms

Provenance statements are a great idea. Providing provenance should become part of the minimum bar for publishing packages. If you maintain an open source NPM package, have you added provenance yet?

If you already use GitHub Actions or GitLab CI/CD you have no excuse. If you currently build locally, you may be surprised how easy it is to get a build running on GitHub Actions.

Next time I’ll show you what happened when I added provenance to my open source package.

Trusting GitHub

Given what happened with SolarWinds, how do you feel about an ecosystem where everything is dependent on GitHub? If a nation state attacker compromised the GitHub build system, they could do whatever they wanted.

In some sense it’s too late. Git is overwhelmingly the most popular version control system and GitHub is the most popular git hosting platform, with GitLab a long way behind in second place.

If GitHub is compromised, we’ve already lost.