DynamoDB is AWS’s flagship, serverless, horizontally scalable, NoSQL database. The work that ultimately led to the release of DynamoDB in 2012, started in 2004. Amazon was growing rapidly and finding it hard to scale their relational databases. The development of DynamoDB was driven by the observation that 70% of Amazon’s queries were key-value lookups using a primary key to return a single row. Another 20% returned a set of rows from a single table.

DynamoDB was built to satisfy these two use cases while claiming to achieve virtually unlimited scalability and consistent single digit milliseconds latency.

DynamoDB Data Model

DynamoDB stores items which consist of multiple attributes. DynamoDB supports ten different data types for attributes. These include simple scalar types (string, number, binary, boolean and null), document types equivalent to JSON (list is equivalent to a JSON array, map is equivalent to a JSON object), and three set types (string set, number set, binary set). Sets can contain any number of unique values. Only top level string, number and binary attributes can be used as keys. Items have an overall size limit of 400KB.

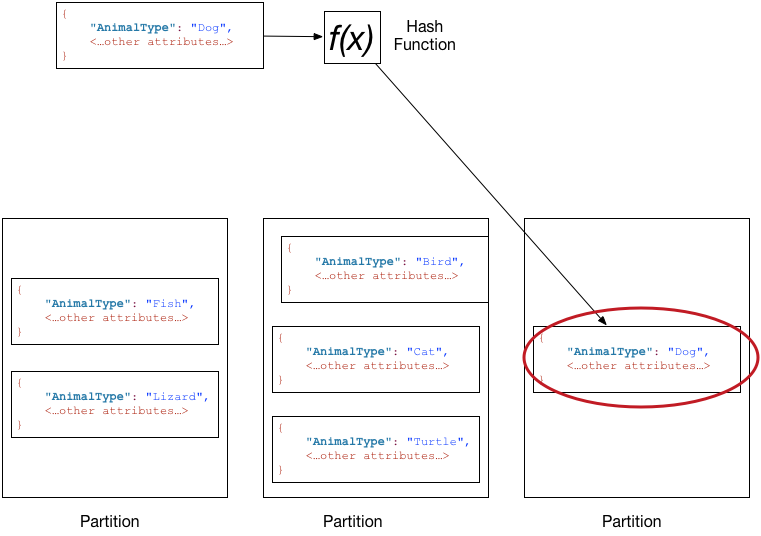

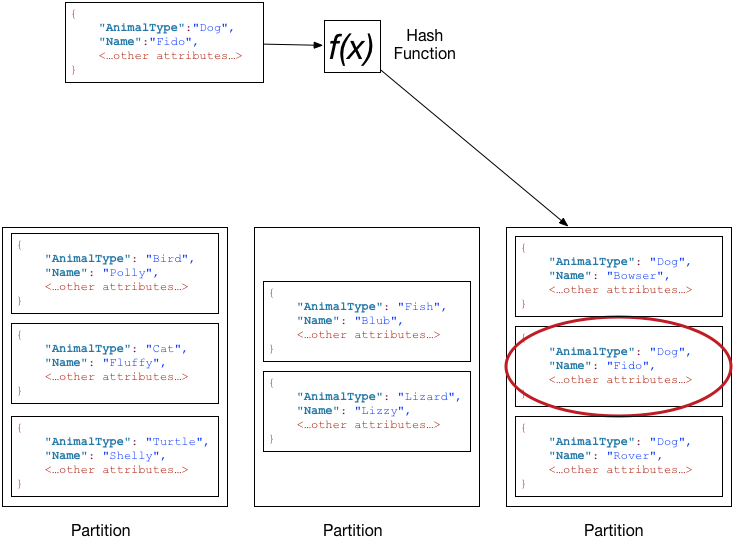

The DynamoDB data model is a direct reflection of the original requirements. Every DynamoDB primary key includes a partition attribute. DynamoDB maps each item to a dedicated storage partition by hashing the partition attribute. As the table grows in size, DynamoDB automatically adds more storage partitions, redistributing the data as needed. This allows DynamoDB to scale horizontally pretty much indefinitely.

Every query must include a specific value for the partition attribute. This means that each query can be handled by routing it to the storage instance that hosts the corresponding storage partition. This, together with an eventual consistency model, is what ensures DynamoDB’s predictable, low latency response. This is all that is required to handle the first use case of key-value lookups returning a single row.

The primary key can optionally include a sort attribute to create a composite primary key. Data is maintained in sorted order in each storage partition. Querying a table that uses a composite primary key can return multiple items in sorted order. You can retrieve all items with the same partition attribute, or a subset of items by specifying conditions on the sort attribute. This covers the second use case.

Since it’s initial release, DynamoDB has steadily added additional features. These include automatically maintained secondary indexes, batch writes, query filters, conditional writes, optional strongly consistent reads, change data capture, optional transactions, and support for a subset of the PartiQL SQL compatible query language.

How Not To Do It

We now have a superficial understanding of the DynamoDB data model. How can we use it to implement our database backed grid view?

A natural starting point would be to try and find a logical partitioning in our data model and map that to a DynamoDB partition. In our case, all our data is organized into tenants, with all queries working within the scope of a tenant. If we use tenant id as a partition attribute, we isolate each customer’s workload into separate partitions.

DynamoDB doesn’t work that way. Each DynamoDB storage partition manages up to 10GB of data and has limited IO capacity (6000 reads totalling 24MB per second, 1000 writes totalling 1MB per second). Each DynamoDB server instance manages many storage partitions from multiple AWS customers. This relatively fine grained partitioning is what allows DynamoDB to scale seamlessly. Storage partitions are constantly moved around, split and merged, without your application having to be aware of what’s going on. This contrasts painfully with something like MongoDB where databases are sharded over physical server instances and scaling up to add more instances can take months of careful planning.

You’re not achieving any meaningful isolation by partitioning by tenant and you’ve severely restricted the expressiveness of your queries. Ideally you want to sustain even loads across storage partitions1. Partitioning by tenant does the opposite.

Document Design

DynamoDB is a schemaless, NoSQL database with support for JSON like document types. We can use the same sort of JSON based structures that we used with Postgres JSON and MongoDB. We can only index top level attributes, so we need to flatten the structure to something like this:

{

"id": "020e",

"name": "Needs Painting",

"project": "35e9",

"num": 1,

"state": "open",

"d1": "2023-05-01",

"d2": "2023-06-01"

}

Our issue table can use id as the partition key, so we’re spreading the load as evenly as possible. Once again we’d need 400 indexes to be able to sort by every custom field. We know that’s a bad idea. So bad, that DynamoDB doesn’t allow it. The default quota allows 20 indexes per table. There is stern advice to limit the number of indexes you create.

There’s no MongoDB like Multikey Index. Each item can appear at most once in each index.

It looks like this is a dead end.

Classic Design

What if we take our (slightly de-) normalized relational database design and and transpose it into a DynamoDB design? That gives us five separate tables: Tenant, Project, Issue, Attribute Definition and Attribute Value. However, there’s no support for joins. How do you retrieve an issue together with all it’s custom field values?

You implement the join yourself, in your app server. Here’s what our sample Issue table looks like

| Issue Id (PK) | name | project | num | state |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 020e | Needs Painting | 35e9 | 1 | open |

| 3544 | Launch new newspaper! | 7b7e | 1 | closed |

| 67d1 | Check for rust | 35e9 | 2 | closed |

| 83a4 | Hire reporter for showbiz desk | 7b7e | 2 | open |

| af34 | Girder needs replacing | 35e9 | 3 | open |

and here’s the corresponding Attribute Value table2.

| Issue Id (PK) | Attribute Definition Id (SK) | String Value | Number Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 020e | 3812 | 2023-05-01 | |

| 020e | 882a | 2023-06-01 | |

| 67d1 | 3812 | 2023-05-02 | |

| 67d1 | 882a | 2023-06-02 | |

| af34 | 3fe6 | 42 | |

| af34 | 47e5 | Approved |

In our relational design we used a composite key of (issue id, attribute definition id) for attribute values. In DynamoDB I’ve used issue id for the partition key and attribute definition id for the sort key. That means a single query on issue id will return all the attribute values for the issue. We can get the issue and all custom field values using two queries, which our app server can issue in parallel.

You may be wondering why I have two separate value columns, one for values represented as strings, and one for values represented as numbers. Isn’t DynamoDB a schemaless database? Can’t I have a common DynamoDB attribute which is a string in some items and a number in others?

DynamoDB is schemaless apart from the partition key and sort key of a table or index. Those must have a consistent type defined when the table or index is created. Value isn’t a key in this table but it will be in the indexes I’m about to create.

As in the relational design, we’re going to need an index so we can retrieve issues in custom field order. We need separate indexes for string and number values. DynamoDB indexes are inherently partial. Items are only indexed if they have the index key attributes defined.

| Attribute Definition Id (PK) | String Value (SK) | Issue Id |

|---|---|---|

| 3812 | 2023-05-01 | 020e |

| 3812 | 2023-05-02 | 67d1 |

| 47e5 | Approved | af34 |

| 882a | 2023-06-01 | 020e |

| 882a | 2023-06-02 | 67d1 |

| Attribute Definition Id (PK) | Number Value (SK) | Issue Id |

|---|---|---|

| 3fe6 | 42 | af34 |

There’s no query planner in DynamoDB. The application directly queries an index in the same way you would a table. We can query the appropriate index with an attribute definition id to get all issues that have that custom field, in value order.

We could have thousands of issues, so obviously we’ll need to paginate. DynamoDB has direct support for pagination. To ensure scalability and low latency, DynamoDB’s design philosophy is to prevent you from creating long running queries. There is a limit on the amount of data that a query can return, with built in support for Keyset Pagination. You can also set an explicit limit on the number of items to return, if you prefer.

If the query didn’t complete, the query response includes a LastEvaluatedKey token which you can pass in to a subsequent query using the ExclusiveStartKey parameter. That query will return the next page of items in sort key order.

Unlike a table, items in an index can have duplicate keys. We had to take special care to handle this case when implementing pagination with a relational database. Fortunately, DynamoDB’s pagination implementation handles it for you.

That gets us a page of issue ids in sorted order. Now we have to implement the rest of the join in our app server. For each issue in the page, we’ll need two further queries to get the issue itself and all the custom fields for the issue. All of these subsequent queries can be issued in parallel, but it’s still a lot of queries to manage. DynamoDB supports batch operations for individual item key-value lookups. That would let us retrieve a page of 100 issues with a single API call. However, we still need a separate query per issue to retrieve custom field values.

As with previous implementations, we need a separate query to retrieve the remaining issues that don’t have the custom field we’re sorting on defined. It’s easy enough to create an index on the issues table with project id as the partition key and issue num as the sort key. That lets us page through all the issues on the project in num order. Then, for each page of issues, we can use a batch get to check which issues have the custom field defined and filter them out. Finally, following up with a query per issue to get the custom fields.

I guess now you can appreciate how much work a relational database does for you.

Pre-Joined Table

Is there some way we can reduce the number of queries needed? Look at our Issue and Attribute Value tables again. They both use issue id as a partition key. Why don’t we put them in the same table and avoid having to do the join at query time?

We’ll need to be consistent about the attributes used for keys in the table and it’s indexes. There are two overloaded attributes. The sort key is the project id for an issue and the attribute definition id for an attribute value. Then we have a common Num Value attribute used as issue num for an issue and Number Value for an attribute value.

| Issue Id (PK) | Project-Attribute Id (SK) | String Value | Num Value | name | state |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 020e | 35e9 | 1 | Needs Painting | open | |

| 020e | 3812 | 2023-05-01 | |||

| 020e | 882a | 2023-06-01 | |||

| 3544 | 7b7e | 1 | Launch new newspaper! | closed | |

| 67d1 | 35e9 | 2 | Check for rust | closed | |

| 67d1 | 3812 | 2023-05-02 | |||

| 67d1 | 882a | 2023-06-02 | |||

| 83a4 | 7b7e | 2 | Hire reporter for showbiz desk | open | |

| af34 | 35e9 | 3 | Girder needs replacing | open | |

| af34 | 3fe6 | 42 | |||

| af34 | 47e5 | Approved |

Now we can retrieve both the issue definition and the values of all custom fields using a single query.

We create two indexes as before, using the table sort key as the index partition key and String Value / Num Value as the sort keys. The String Value index is exactly the same as before, containing only attribute value items. However, the Num Value index is overloaded.

| Project-Attribute Id (PK) | Num Value (SK) | Issue Id |

|---|---|---|

| 35e9 | 1 | 020e |

| 35e9 | 2 | 67d1 |

| 35e9 | 3 | af34 |

| 3fe6 | 42 | af34 |

| 7b7e | 1 | 3544 |

| 7b7e | 2 | 83a4 |

The same index lets me lookup issues within a project sorted by issue num, and issues with a specified number attribute definition sorted by number value. As well as reducing the number of queries needed, I have one less table and one less index to manage.

Composite Sort Key

In our previous implementations we tried to sort issues by custom field value and then by num. This was to give the user a sensible ordering in cases with duplicate custom field values. How do we do that with DynamoDB?

With difficulty. DynamoDB has no support for multi-attribute composite sort keys. You have to implement it yourself by adding another attribute that will act as the sort key and populating it with combined values from the attributes you want to sort on. You can replace the other attributes with this combo attribute and deal with unpacking the combined attributes when you need to access them for other purposes. Or you can make your life easier by leaving the other attributes as is. Your application just needs to update the sort key whenever any of the other attributes change.

The usual approach is to make the composite sort key a string. You need to combine the values that make up the sort key in such a way that the resulting string sorts correctly. First, you need to format each value as a string that is lexicographically ordered. ISO format dates are already lexicographically ordered, binary values can be hex encoded and small positive integers can be padded with leading zeros to a fixed length. General solutions for large signed integers and floating point numbers are known but surprisingly fiddly.

Finally, you need to concatenate the formatted strings in order with a separator character that has a UTF-8 encoding smaller than any character used in the formatted strings. AWS examples always use # as a separator with alphanumeric value strings. A more general solution is to use one of the unused control characters like U+0001 “Start of Heading”.

One small benefit of all this mucking around is that all items have a string typed sort attribute so we no longer need separate indexes. Our combined index would look something like this :

| Project-Attribute Id (PK) | Sort String (SK) | Issue Id |

|---|---|---|

| 35e9 | 000001 | 020e |

| 35e9 | 000002 | 67d1 |

| 35e9 | 000003 | af34 |

| 3812 | 2023-05-01#000001 | 020e |

| 3812 | 2023-05-02#000002 | 67d1 |

| 3fe6 | 000042#000003 | af34 |

| 47e5 | Approved#000003 | af34 |

| 7b7e | 000001 | 3544 |

| 7b7e | 000002 | 83a4 |

| 882a | 2023-06-01#000001 | 020e |

| 882a | 2023-06-02#000002 | 67d1 |

If you end up needing to implement a fully general solution, your sort strings will be pretty much unreadable. In that case it might be simpler and more space efficient to look at binary encodings and use a binary type sort key.

Single Table Design

Our journey through DynamoDB design patterns mirrors their historical development. Originally, Classic Design was recommended practice with Pre-Joined Tables and Composite Sort Keys being “use at your own risk” outliers. Roll forward to the present day and recommended practice is the even more out there Single Table Design, which AWS calls the Adjacency List design pattern.

With Pre-Joined tables we stored entities with the same partition key in the same table. That results in an overloaded secondary index which can serve multiple access patterns in one. Single Table Design takes that idea and runs with it by storing all entities in the same table.

The more entities you have, the more you need to generalize the treatment of shared attributes. Each item has an Entity Id, a Related Id and a Sort String. Ids are strings and start with an entity type specific prefix. This is vital for keeping track of which entity is which and ensuring that entities of the same type sort together. The main table uses Entity Id as a partition key and Related Id as the Sort Key. The overloaded secondary index uses Related Id as the partition key and Sort String as the sort key.

Related Id can be whatever you like depending on the access patterns you want to support. It can identify a contained sub-item, as in a Pre-Joined table, or it could be a foreign key to another top level entity used to model a many to one relationship. Need multiple relationships? Add another item for each related entity.

Here’s a single table representation of our sample data. I’ve decided not to duplicate the values in the sort strings into their own attributes, saving space both in the database and this blog post.

| Entity Id (PK) | Related Id (SK) | Sort String | Name | Num | State | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tenant-0807 | * | ACME Engineering | ||||

| tenant-3cc8 | * | Big Media | ||||

| project-35e9 | tenant-0807 | Forth Rail Bridge | ||||

| project-35e9 | xattrib-35e6 | Num Items | 3 | int | ||

| project-35e9 | xattrib-3812 | Start | 1 | date | ||

| project-35e9 | xattrib-47e5 | Sign Off | 4 | text | ||

| project-35e9 | xattrib-882a | End | 2 | date | ||

| project-7b7e | tenant-3cc8 | The Daily News | ||||

| issue-020e | project-35e9 | 000001 | Needs Painting | open | ||

| issue-020e | xvalue-3812 | 2023-05-01#000001 | ||||

| issue-020e | xvalue-882a | 2023-06-01#000001 | ||||

| issue-3544 | project-7b7e | 000001 | Launch new newspaper! | closed | ||

| issue-67d1 | project-35e9 | 000002 | Check for rust | closed | ||

| issue-67d1 | xvalue-3812 | 2023-05-02#000002 | ||||

| issue-67d1 | xvalue-882a | 2023-06-02#000002 | ||||

| issue-83a4 | project-7b7e | 000002 | Hire reporter for showbiz desk | open | ||

| issue-af34 | project-35e9 | 000003 | Girder needs replacing | open | ||

| issue-af34 | xvalue-3fe6 | 000042#000003 | ||||

| issue-af34 | xvalue-47e5 | Approved#000003 |

One table stores all five types of entity.

- The only access pattern that tenants need is a key value lookup so sort string is unused and Related Id is a place holder (you have to define something for a key attribute).

- Projects have tenants as their related id, modelling the one tenant has many projects relationship.

- Projects contain attribute definitions. Attribute Definition ids use xattrib as the prefix so that they always sort after the main project item.

- Issues have projects as their related id, modelling the one project has many issues relationship.

- Issues contain attribute values. Attribute Values have a different prefix (xvalue) to distinguish them from attribute definitions, but have matching ids.

This table supports key-value lookup of tenants, querying a project together with its custom field definitions, and querying an issue together with its custom field values.

Let’s have a look at the index.

| Related Id (PK) | Sort String (SK) | Entity Id |

|---|---|---|

| tenant-0807 | Forth Rail Bridge | project-35e9 |

| tenant-3cc8 | The Daily News | project-7b7e |

| project-35e9 | 000001 | issue-020e |

| project-35e9 | 000002 | issue-67d1 |

| project-35e9 | 000003 | issue-af34 |

| project-7b7e | 000001 | issue-3544 |

| project-7b7e | 000002 | issue-83a4 |

| xattrib-3812 | 2023-05-01#000001 | issue-020e |

| xattrib-3812 | 2023-05-02#000002 | issue-67d1 |

| xattrib-3fe6 | 000042#000003 | issue-af34 |

| xattrib-47e5 | Approved#000003 | issue-af34 |

| xattrib-882a | 2023-06-01#000001 | issue-020e |

| xattrib-882a | 2023-06-02#000002 | issue-67d1 |

This index supports querying projects in a tenant sorted by project name, querying issues in a project sorted by issue num and querying issues in a project sorted on any custom field, with a secondary sort on issue num.

Eventual Consistency

So far we’ve been ignoring the elephant in the room. DynamoDB has an eventual consistency model. What does that mean for our application?

The databases we’ve looked at so far have strong consistency models. When you update a row in a relational database, the change to the row and any related updates to indexes appear to happen at the same time. An application either sees the database state before any change has happened, or the state after all the changes have been applied. Once the application has seen the changed data, no query will return data from the earlier state. In particular, if an application performs an update and then queries the updated state, it will never see data from before the update (known as read after write consistency).

You can’t rely on any of this with DynamoDB. By default, reads are eventually consistent. Data is replicated asynchronously across multiple replica storage partitions for redundancy. An eventually consistent read may retrieve data from a replica that hasn’t been updated yet. You can optionally perform a strongly consistent read (at twice the cost and using twice the IO) which does guarantee read after write consistency when querying a table.

The global secondary indexes that we’ve been using are always eventually consistent. If you query an index after an update, your change may not be reflected yet.

Your application needs to be designed to cope with eventual consistency. What does that mean in practice? In most cases, it doesn’t matter that changes made by other clients are eventually consistent. The end user doesn’t know when those changes were made, so won’t notice if they show up a few seconds late. In our case the grid view is populated by querying an index. If a new issue has been added but the index hasn’t been updated yet, it won’t be visible. If a custom field value has been changed, but the index hasn’t been updated yet, the issue may appear out of order. These are rare occurrences with minimal impact. Everything will be sorted out when the UI is next refreshed.

A more significant problem is that each issue is represented by multiple items: one containing the fixed fields and then one per custom field value. By default, updates to a single item are atomic, updates to multiple items (even if batched into a single API call) are not. If multiple clients are updating the same issue at roughly the same time, the result may be a mixture of their changes, rather than being entirely one or the other.

Whether that matters depends on your application. If all fields are entirely independent then maybe it’s not a problem. If there are inter-field consistency constraints it definitely is a problem. DynamoDB does support optional ACID transactions that guarantee atomic updates for up to 100 items at a time. The transaction uses a two phase protocol which doubles the cost and uses twice the IO compared to the base operations.

In our case, issues can have up to 400 custom fields which means an issue is represented by up to 401 items. If more than 100 of those are changed, it’s not possible to perform an atomic update.

Document Design with DynamoDB Streams

It’s annoying that we can’t perform atomic updates of our multi-item issues. An issue with 400 custom fields would easily fit inside the 400KB per item limit (even with 100 maximum length text fields of 1KB each). Is there really no way to make a simple document design work?

Well, there is. As long as you’re prepared to do some extra work. DynamoDB Streams provide access to item-level change data capture records in near-real time. DynamoDB ensures that each change is written to the stream exactly once and that item modification records appear in the same order as the modifications to the item. DynamoDB Streams is integrated with AWS Lambda. You can write a simple Lambda function that reacts to an item change and performs a corresponding update elsewhere. DynamoDB and Lambda will scale the number of parallel Lambda invocations as needed to keep up with the rate of changes, while also making sure that changes to a specific item are processed in sequence.

Which is cool, but how does it help us?

We can use DynamoDB streams to build our own MultiKey index. Let’s start with a classic design that has Tenant, Project and Issue tables. We can use the same issue schema that we used with our JSON relational database implementation.

| id (PK) | name | project | num | state | custom_fields |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 020e | Needs Painting | 35e9 | 1 | open | {“3812”:”2023-05-01”,”882a”:”2023-06-01”} |

| 3544 | Launch new newspaper! | 7b7e | 1 | closed | |

| 67d1 | Check for rust | 35e9 | 2 | closed | {“3812”:”2023-05-02”,”882a”:”2023-06-02”} |

| 83a4 | Hire reporter for showbiz desk | 7b7e | 2 | open | |

| af34 | Girder needs replacing | 35e9 | 3 | open | {“3fe6”:42,”47e5”:”Approved”} |

As well as giving us per issue atomic updates, having each issue represented by a single item means we can use batch get to retrieve a page of issues with a single API call. Now we only need two API calls to retrieve a page of issues sorted by custom field. Although first, we’ll need to build an index.

We create a separate Issue Attrib Index table that we can query as if it was an index. As this is a real table, rather than a DynamoDB index, we need to ensure that every item has a unique primary key. We do that by using a composite sort key that includes attribute value and issue num. The Issue Attrib Index table is only written to by a Lambda function that reacts to changes in the Issue table via DynamoDB streams. We can use whatever format we like in the issue table. We don’t need attributes in the index table to match those in the issue table. We don’t need to have a 1:1 mapping between an item in the issue table and an item in the index table.

| Attrib Id (PK) | Sort String (SK) | Issue Id |

|---|---|---|

| 3812 | 2023-05-01#000001 | 020e |

| 3812 | 2023-05-02#000002 | 67d1 |

| 3fe6 | 000042#000003 | af34 |

| 47e5 | Approved#000003 | af34 |

| 882a | 2023-06-01#000001 | 020e |

| 882a | 2023-06-02#000002 | 67d1 |

The Lambda function processes DynamoDB Stream Records. Each record includes the primary key of the item that has changed, the previous state of the item and the new state of the item. A separate part of the record has other metadata, including whether the item is being inserted, modified or removed. The Lambda logic is straight forward:

- If the item is being inserted, insert an item into the index table for each custom field in the new version of the item

- If the item is being removed, remove index items for each custom field in the old version of the item

- If the item is being modified

- Remove index items where custom fields exist in the old version of the item but not the new version

- Insert index items where custom fields exist in the new version of the item but not the old version

- Update index items where custom fields exist in both old and new versions of the item and either the custom field value has changed or the issue num has changed

The lambda logic is also responsible for combining custom field value and issue num into a composite sort key. All the unpleasantness involved can be tucked away in the Lambda function and hidden from the rest of the application.

The DynamoDB-Lambda integration also supports event filtering. We can configure the stream to ignore events for items that don’t have any custom fields.

We can mix and match regular DynamoDB indexes with our custom indexes. We don’t need any custom behavior for an index of issues per project in num order, so we can use a regular DynamoDB index for that.

I’ve worked with a couple of teams that used DynamoDB streams and Lambda to synchronize changes from one DynamoDB table to another. They found it to be absolutely rock solid. No duplicated records, no missing records, no records out of sequence. The only thing to be aware of is that stream records are buffered for up to 24 hours. If the operations team misconfigure something, or the destination table is throttled and data starts to back up, you don’t have much time to sort the problem out. Make sure you have appropriate monitoring and alerting configured.

Conclusion

DynamoDB is a kit of parts that you can use in all sorts of interesting ways. It really does scale seamlessly from nothing to whatever load you can imagine. We’ve looked at four different ways of implementing a database backed grid view, which each have different trade offs.

The downside is that you need a deep understanding of all the access patterns your application needs up front. You will carefully design your schema and indexing strategies to cover all the access patterns with as few tables and indexes as you can. The only query planner you have is in your head. Whatever plan you come up with needs to be explicitly coded in your app server.

Of course requirements change over time. A relational database with a normalized design will adapt gracefully to support new entities and relationships. You can always come up with a SQL query that will satisfy whatever new access pattern you need. In contrast, with DynamoDB, seemingly minor changes can necessitate a complete redesign of your schema, migration of existing data and rewrite of the data access layer in your app server. DynamoDB encourages “clever” solutions that can be hard to understand and maintain.

So, what should a team do? If you have a well understood problem with requirements that you can honestly say are not going to change every six months, then go for it. Document your access patterns, figure out a schema, put a prototype together. You’ll be pleased by how well the system scales and how little operational overhead is involved.

On the other hand, if you’re like most teams in the startup and SaaS spaces, desperately pivoting and evolving to find market fit, DynamoDB might not be right for you. It’s not a bad idea to start with a boring old relational database which can keep your development velocity high while you evolve your data model and change direction frequently. At low scale, a relational database will handle everything you throw at it, even with shockingly badly written queries. Then, if you find success, understand your problem well, and need to really scale, it might be a good time to look at DynamoDB.

Footnotes

-

This is less of a problem now that DynamoDB supports adaptive capacity. DynamoDB will split storage partitions (on sort key if all items have the same partition key) to separate high traffic items. It can even go so far as to isolate a single super high traffic item in its own dedicated storage partition. ↩

-

In this and subsequent tables I have highlighted rows corresponding to alternate entities. Hopefully it makes it easier to see how multiple items end up representing a single entity. ↩